Very little is known about the Library of Alexandria during the time of the Roman Principate (27 BC–284 AD). The emperor Claudius (ruled 41–54 AD) is recorded to have built an addition onto the Library, but it seems that the Library of Alexandria's general fortunes followed those of the city of Alexandria itself.

The same was evidently the case even for the position of head librarian; the only known head librarian from the Roman Period was a man named Tiberius Claudius Balbilus, who lived in the middle of the first century AD and was a politician, administrator, and military officer with no record of substantial scholarly achievements.

In 272 AD, the emperor Aurelian fought to recapture the city of Alexandria from the forces of the Palmyrene Queen Zenobia.

Scattered references indicate that, sometime in the fourth century, an institution known as the "Mouseion" may have been reestablished at a different location somewhere in Alexandria. Nothing, however, is known about the characteristics of this organization.

In 642 AD, Alexandria was captured by the Muslim army of 'Amr ibn al-'As. Several later Arabic sources describe the library's destruction by the order of Caliph Omar.

The earliest known surviving source of information on the founding of the Library of Alexandria is the pseudepigraphic Letter of Aristeas, which was composed between c. 180 and c. 145 BC.

It claims the Library was founded during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter (c. 323–c. 283 BC) and that it was initially organized by Demetrius of Phalerum, a student of Aristotle who had been exiled from Athens and taken refuge in Alexandria within the Ptolemaic court.

The first recorded head librarian was Zenodotus of Ephesus. Zenodotus's main work was devoted to the establishment of canonical texts for the Homeric poems and the early Greek lyric poets. Most of what is known about him come from later commentaries that mention his preferred readings of particular passages.

Zenodotus is known to have written a glossary of rare and unusual words, which was organized in alphabetical order, making him the first person known to have employed alphabetical order as a method of organization.

After Zenodotus either died or retired, Ptolemy II Philadelphus appointed Apollonius of Rhodes (lived c. 295–c. 215 BC), a native of Alexandria and a student of Callimachus, as the second head librarian of the Library of Alexandria.

Philadelphus also appointed Apollonius of Rhodes as the tutor to his son, the future Ptolemy III Euergetes.

The Library of Alexandria was not affiliated with any particular philosophical school and, consequently, scholars who studied there had considerable academic freedom. They were, however, subject to the authority of the king.

One likely apocryphal story is told of a poet named Sotades who wrote an obscene epigram making fun of Ptolemy II for marrying his sister Arsinoe II. Ptolemy II is said to have jailed him and, after he escaped, sealed him in a lead jar and dropped him into the sea.

The third head librarian, Eratosthenes of Cyrene (lived c. 280–c. 194 BC), is best known today for his scientific works, but he was also a literary scholar.

After the Battle of Raphia in 217 BC, Ptolemaic power became increasingly unstable. There were uprisings among segments of the Egyptian population and, in the first half of the second century BC, connection with Upper Egypt became largely disrupted. Ptolemaic rulers also began to emphasize the Egyptian aspect of their nation over the Greek aspect.

Consequently, many Greek scholars began to leave Alexandria for safer countries with more generous patronages.

Aristophanes of Byzantium (lived c. 257–c. 180 BC) became the fourth head librarian sometime around 200 BC.

Aristarchus of Samothrace (lived c. 216–c. 145 BC) was the sixth head librarian.

In 145 BC, however, Aristarchus became caught up in a dynastic struggle in which he supported Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator as the ruler of Egypt.

Ptolemy VII was murdered and succeeded by Ptolemy VIII Physcon, who immediately set about punishing all those who had supported his predecessor, forcing Aristarchus to flee Egypt and take refuge on the island of Cyprus, where he died shortly thereafter.

Another one of Aristarchus's pupils, Apollodorus of Athens (c. 180–c. 110 BC), went to Alexandria's greatest rival, Pergamum, where he taught and conducted research. This diaspora prompted the historian Menecles of Barce to sarcastically comment that Alexandria had become the teacher of all Greeks and barbarians alike.

Aristarchus's student Dionysius Thrax (c. 170–c. 90 BC) established a school on the Greek island of Rhodes. Dionysius Thrax wrote the first book on Greek grammar, a succinct guide to speaking and writing clearly and effectively. This book remained the primary grammar textbook for Greek schoolboys until as late as the twelfth century AD. The Romans based their grammatical writings on it, and its basic format remains the basis for grammar guides in many languages even today.

Several of the later Ptolemies used the position of the head librarian as a mere political plum to reward their most devoted supporters.

Ptolemy VIII appointed a man named Cydas, one of his palace guards, as head librarian.

Ptolemy IX Soter II (ruled 88–81 BC) is said to have given the position to a political supporter. Eventually, the position of head librarian lost so much of its former prestige that even contemporary authors ceased to take interest in recording the terms of office for individual head librarians.

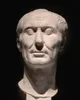

In 48 BC, during Caesar's Civil War, Julius Caesar was besieged at Alexandria. His soldiers set fire to some of the Egyptian ships docked in the Alexandrian port while trying to clear the wharves to block the fleet belonging to Cleopatra's brother Ptolemy XIV.

This fire purportedly spread to the parts of the city nearest to the docks, causing considerable devastation.

Furthermore, Plutarch records in his Life of Marc Antony that, in the years leading up to the Battle of Actium in 33 BC, Mark Antony was rumored to have given Cleopatra all 200,000 scrolls in the Library of Pergamum.

Plutarch himself notes that his source for this anecdote was sometimes unreliable and it is possible that the story may be nothing more than propaganda intended to show that Mark Antony was loyal to Cleopatra and Egypt rather than to Rome.

Casson, however, argues that, even if the story was made up, it would not have been believable unless the Library still existed. Edward J. Watts argues that Mark Antony's gift may have been intended to replenish the Library's collection after the damage to it caused by Caesar's fire roughly a decade and a half prior.