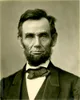

History of Abraham Lincoln

Sunday Feb 12, 1809 to Saturday Apr 15, 1865

U.S.

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American statesman and lawyer who served as the 16th president of the United States (1861–1865). Lincoln led the nation through its greatest moral, constitutional, and political crisis in the American Civil War. He succeeded in preserving the Union, abolishing slavery, bolstering the federal government, and modernizing the U.S. economy.

Elizabethtown, Kentucky, U.S. 1806 Parents moved to Elizabethtown

Elizabethtown, Kentucky, U.S. 1806 The heritage of Lincoln's mother Nancy remains unclear, but it is widely assumed that she was the daughter of Lucy Hanks. Thomas and Nancy married on June 12, 1806, in Washington County, and moved to Elizabethtown, Kentucky. They had three children: Sarah, Abraham, and Thomas, who died an infant.

Hodgenville, Kentucky, U.S. Monday Feb 13, 1809 Kentucky, U.S. 1800s Hurricane Township, Perry County, Indiana, U.S. 1816 Indiana, U.S. Monday Oct 5, 1818 U.S. Friday Dec 3, 1819 Indiana, U.S. 1827 Lincoln State Park, Indiana, US Sunday Jan 20, 1828 Indiana, U.S. 1830 Lincoln took responsibility for chores

Indiana, U.S. 1830 As a teen, Lincoln took responsibility for chores, and customarily gave his father all earnings from work outside the home until he was 21. Lincoln was tall, strong, and athletic, and became adept at using an ax. He gained a reputation for strength and audacity after winning a wrestling match with the renowned leader of ruffians known as "the Clary's Grove boys".

Illinois, U.S. Mar, 1830 Coles County, Illinois, U.S. 1831 New Salem, Illinois, U.S. 1831 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. 1831 New Salem, Illinois, U.S. 1832 Illinois, U.S. Mar, 1832 Lincoln entered politics

Illinois, U.S. Mar, 1832 Although the economy was booming, the business struggled and Lincoln eventually sold his share. That March he entered politics, running for the Illinois General Assembly, advocating navigational improvements on the Sangamon River. He could draw crowds as a raconteur, but he lacked the requisite formal education, powerful friends, and money, and lost the election.

Illinois, U.S. 1832 Lincoln briefly interrupted his campaign to serve as a captain in the Illinois Militia

Illinois, U.S. 1832 Lincoln briefly interrupted his campaign to serve as a captain in the Illinois Militia during the Black Hawk War. When he returned to his campaign and first speech, he observed a supporter in the crowd under attack, grabbed the assailant by his "neck and the seat of his trousers" and tossed him. Lincoln finished eighth out of 13 candidates (the top four were elected), though he received 277 of the 300 votes cast in the New Salem precinct.

Illinois, U.S. 1834 Lincoln's second state house campaign

Illinois, U.S. 1834 Lincoln's second state house campaign in 1834, this time as a Whig, was a success over a powerful Whig opponent. Then followed his four terms in the Illinois House of Representatives for Sangamon County. He championed construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, and later was a Canal Commissioner. He voted to expand suffrage beyond white landowners to all white males, but adopted a "free soil" stance opposing both slavery and abolition.

New Salem, Illinois, U.S. 1835 Illinois, U.S. Wednesday Aug 26, 1835 Illinois, U.S. 1836 Illinois, U.S. 1837 "The Institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy"

Illinois, U.S. 1837 In 1837 Lincoln declared, "The Institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy, but the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than abate its evils." He echoed Henry Clay's support for the American Colonization Society which advocated a program of abolition in conjunction with settling freed slaves in Liberia.

Illinois, U.S. 1840 Springfield, Illinois, U.S. Saturday Nov 5, 1842 Illinois, U.S. 1843 Springfield, Illinois, U.S. Wednesday Aug 2, 1843 Springfield, Illinois, U.S. 1844 Lincoln began practicing law with William Herndon

Springfield, Illinois, U.S. 1844 Lincoln emerged as a formidable trial combatant during cross-examinations and closing arguments. He partnered several years with Stephen T. Logan, and in 1844 began his practice with William Herndon, "a studious young man".

Springfield, Illinois, U.S. 1844 Springfield, Illinois, U.S. Wednesday Mar 11, 1846 U.S. 1846 Illinois, U.S. 1846 Lincoln won election

Illinois, U.S. 1846 Lincoln not only pulled off his strategy of gaining the nomination in 1846, but also won election. He was the only Whig in the Illinois delegation, but as dutiful as any, participated in almost all votes and made speeches that toed the party line. Lincoln had pledged in 1846 to serve only one term in the House.

U.S. 1846 U.S. Wednesday Dec 23, 1846 Spot Resolutions

U.S. Wednesday Dec 23, 1846 Lincoln emphasized his opposition to Polk by drafting and introducing his Spot Resolutions. The war had begun with a Mexican slaughter of American soldiers in territory disputed by Mexico, and Polk insisted that Mexican soldiers had "invaded our territory and shed the blood of our fellow-citizens on our soil". Lincoln demanded that Polk show Congress the exact spot on which blood had been shed and prove that the spot was on American soil. The resolution was ignored in both Congress and the national papers, and it cost Lincoln political support in his district. One Illinois newspaper derisively nicknamed him "spotty Lincoln". Lincoln later regretted some of his statements, especially his attack on presidential war-making powers.

U.S. 1848 U.S. 1849 U.S. Sep, 1850 Springfield, Illinois, U.S. Sunday Dec 22, 1850 Springfield, Illinois, U.S. Tuesday Apr 5, 1853 U.S. Tuesday Mar 21, 1854 U.S. May, 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act

U.S. May, 1854 In his 1852 eulogy for Clay, Lincoln highlighted the latter's support for gradual emancipation and opposition to "both extremes" on the slavery issue. As the slavery debate in the Nebraska and Kansas territories became particularly acrimonious, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed popular sovereignty as a compromise; the measure would allow the electorate of each territory to decide the status of slavery. The legislation alarmed many Northerners, who sought to prevent the resulting spread of slavery, but Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act narrowly passed Congress in May 1854.

Illinois, U.S. 1854 Lincoln was elected to the Illinois legislature but declined to take his seat

Illinois, U.S. 1854 In 1854 Lincoln was elected to the Illinois legislature but declined to take his seat. The year's elections showed the strong opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and in the aftermath, Lincoln sought election to the United States Senate.

Peoria, Illinois, U.S. Oct, 1854 Peoria Speech

Peoria, Illinois, U.S. Oct, 1854 Lincoln did not comment on the act until months later in his "Peoria Speech" in October 1854. Lincoln then declared his opposition to slavery which he repeated en route to the presidency. He said the Kansas Act had a "declared indifference, but as I must think, a covert real zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world ..." Lincoln's attacks on the Kansas–Nebraska Act marked his return to political life.

Kansas and Missouri, U.S. 1856 Bloomington, Illinois, U.S. Friday May 30, 1856 Bloomington Convention

Bloomington, Illinois, U.S. Friday May 30, 1856 As the 1856 elections approached, Lincoln joined the Republicans and attended the Bloomington Convention, which formally established the Illinois Republican Party. The convention platform endorsed Congress's right to regulate slavery in the territories and backed the admission of Kansas as a free state.

Bloomington, Illinois, U.S. Friday May 30, 1856 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. Wednesday Jun 18, 1856 June 1856 Republican National Convention

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. Wednesday Jun 18, 1856 At the June 1856 Republican National Convention, though Lincoln received support to run as vice president, John C. Frémont and William Dayton comprised the ticket, which Lincoln supported throughout Illinois. The Democrats nominated former Secretary of State James Buchanan and the Know-Nothings nominated former Whig President Millard Fillmore.

Illinois, U.S. 1850s U.S. 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford

U.S. 1857 Dred Scott was a slave whose master took him from a slave state to a free territory under the Missouri Compromise. After Scott was returned to the slave state he petitioned a federal court for his freedom. His petition was denied in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857). Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in the decision wrote that blacks were not citizens and derived no rights from the Constitution. While many Democrats hoped that Dred Scott would end the dispute over slavery in the territories, the decision sparked further outrage in the North. Lincoln denounced it as the product of a conspiracy of Democrats to support the Slave Power. He argued the decision was at variance with the Declaration of Independence; he said that while the founding fathers did not believe all men equal in every respect, they believed all men were equal "in certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness".

Springfield, Illinois, U.S. Thursday Jun 17, 1858 Lincoln's House Divided Speech

Springfield, Illinois, U.S. Thursday Jun 17, 1858 Accepting the nomination, Lincoln delivered his House Divided Speech, with the biblical reference Mark 3:25, "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other". The speech created a stark image of the danger of disunion. The stage was then set for the election of the Illinois legislature which would, in turn, select Lincoln or Douglas. When informed of Lincoln's nomination, Douglas stated, "[Lincoln] is the strong man of the party ... and if I beat him, my victory will be hardly won."

Illinois, U.S. 1858 Defending William "Duff" Armstrong

Illinois, U.S. 1858 Lincoln argued in an 1858 criminal trial, defending William "Duff" Armstrong, who was on trial for the murder of James Preston Metzker. The case is famous for Lincoln's use of a fact established by judicial notice to challenge the credibility of an eyewitness. After an opposing witness testified to seeing the crime in the moonlight, Lincoln produced a Farmers' Almanac showing the moon was at a low angle, drastically reducing visibility. Armstrong was acquitted.

U.S. 1858 Douglas was up for re-election in the U.S. Senate

U.S. 1858 In 1858 Douglas was up for re-election in the U.S. Senate, and Lincoln hoped to defeat him. Many in the party felt that a former Whig should be nominated in 1858, and Lincoln's 1856 campaigning and support of Trumbull had earned him a favor. Some eastern Republicans supported Douglas from his opposition to the Lecompton Constitution and admission of Kansas as a slave state. Many Illinois Republicans resented this eastern interference. For the first time, Illinois Republicans held a convention to agree upon a Senate candidate, and Lincoln won the nomination with little opposition.

Illinois, U.S. May, 1859 Illinois Staats-Anzeiger

Illinois, U.S. May, 1859 In May 1859, Lincoln purchased the Illinois Staats-Anzeiger, a German-language newspaper that was consistently supportive; most of the state's 130,000 German Americans voted Democratic but the German-language paper mobilized Republican support. In the aftermath of the 1858 election, newspapers frequently mentioned Lincoln as a potential Republican presidential candidate, rivaled by William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates, and Simon Cameron. While Lincoln was popular in the Midwest, he lacked support in the Northeast, and was unsure whether to seek the office.

U.S. 1859 Defense of Simeon Quinn

U.S. 1859 Leading up to his presidential campaign, Lincoln elevated his profile in an 1859 murder case, with his defense of Simeon Quinn "Peachy" Harrison who was a third cousin; Harrison was also the grandson of Lincoln's political opponent, Rev. Peter Cartwright. Harrison was charged with the murder of Greek Crafton who, as he lay dying of his wounds, confessed to Cartwright that he had provoked Harrison. Lincoln angrily protested the judge's initial decision to exclude Cartwright's testimony about the confession as inadmissible hearsay. Lincoln argued that the testimony involved a dying declaration and was not subject to the hearsay rule. Instead of holding Lincoln in contempt of court as expected, the judge, a Democrat, reversed his ruling and admitted the testimony into evidence, resulting in Harrison's acquittal.

U.S. Saturday Jan 21, 1860 Cooper Union, New York, U.S. Tuesday Feb 28, 1860 Cooper Union speech

Cooper Union, New York, U.S. Tuesday Feb 28, 1860 On February 27, 1860, powerful New York Republicans invited Lincoln to give a speech at Cooper Union, in which he argued that the Founding Fathers had little use for popular sovereignty and had repeatedly sought to restrict slavery. He insisted that morality required opposition to slavery, and rejected any "groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong". Many in the audience thought he appeared awkward and even ugly. But Lincoln demonstrated intellectual leadership that brought him into contention. Journalist Noah Brooks reported, "No man ever before made such an impression on his first appeal to a New York audience".

Decatur, Illinois, U.S. Thursday May 10, 1860 Illinois Republican State Convention

Decatur, Illinois, U.S. Thursday May 10, 1860 On May 9–10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur. Lincoln's followers organized a campaign team led by David Davis, Norman Judd, Leonard Swett, and Jesse DuBois, and Lincoln received his first endorsement.

Chicago, Illinois, U.S. Saturday May 19, 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago

Chicago, Illinois, U.S. Saturday May 19, 1860 On May 18, at the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Lincoln won the nomination on the third ballot, beating candidates such as Seward and Chase. A former Democrat, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, was nominated for vice president to balance the ticket. Lincoln's success depended on his campaign team, his reputation as a moderate on the slavery issue, and his strong support for internal improvements and the tariff.

U.S. Wednesday Nov 7, 1860 Lincoln was elected the 16th president

U.S. Wednesday Nov 7, 1860 On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected the 16th president. He was the first Republican president and his victory was entirely due to his support in the North and West; no ballots were cast for him in 10 of the 15 Southern slave states, and he won only two of 996 counties in all the Southern states. Lincoln received 1,866,452 votes, or 39.8% of the total in a four-way race, carrying the free Northern states, as well as California and Oregon. His victory in the electoral college was decisive: Lincoln had 180 votes to 123 for his opponents.

U.S. 1860 Lincoln and the Republicans rejected the proposed Crittenden Compromise

U.S. 1860 Attempts at compromise followed but Lincoln and the Republicans rejected the proposed Crittenden Compromise as contrary to the Party's platform of free-soil in the territories. Lincoln said, "I will suffer death before I consent ... to any concession or compromise which looks like buying the privilege to take possession of this government to which we have a constitutional right."

U.S. Friday Dec 21, 1860 U.S. 1861 U.S. Saturday Feb 2, 1861 U.S. Saturday Feb 9, 1861 The Confederacy (Present Day U.S.) Sunday Feb 10, 1861 Washington D.C., U.S. Sunday Feb 24, 1861 U.S. Sunday Mar 3, 1861 Corwin Amendment

U.S. Sunday Mar 3, 1861 Lincoln tacitly supported the Corwin Amendment to the Constitution, which passed Congress and was awaiting ratification by the states when Lincoln took office. That doomed amendment would have protected slavery in states where it already existed. A few weeks before the war, Lincoln sent a letter to every governor informing them Congress had passed a joint resolution to amend the Constitution.

Washington D.C., U.S. Monday Mar 4, 1861 U.S. Tuesday Mar 5, 1861 Abraham Lincoln's first inaugural address

U.S. Tuesday Mar 5, 1861 Lincoln directed his inaugural address to the South, proclaiming once again that he had no inclination to abolish slavery in the Southern states: Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by the accession of a Republican Administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that "I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so." — First inaugural address, 4 March 1861.

Charleston, South Carolina, U.S. Saturday Apr 13, 1861 Civil War Begin

Charleston, South Carolina, U.S. Saturday Apr 13, 1861 Major Robert Anderson, commander of the Union's Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, sent a request for provisions to Washington, and Lincoln's order to meet that request was seen by the secessionists as an act of war. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces fired on Union troops at Fort Sumter and began the fight.

U.S. Monday Apr 15, 1861 Lincoln called on the states to send detachments totaling 75,000 troops

U.S. Monday Apr 15, 1861 On April 15, Lincoln called on the states to send detachments totaling 75,000 troops to recapture forts, protect Washington, and "preserve the Union", which, in his view, remained intact despite the seceding states. This call forced states to choose sides. Virginia seceded and was rewarded with the designation of Richmond as the Confederate capital, despite its exposure to Union lines. North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas followed over the following two months. Secession sentiment was strong in Missouri and Maryland, but did not prevail; Kentucky remained neutral. The Fort Sumter attack rallied Americans north of the Mason-Dixon line to defend the nation.

Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. Friday Apr 19, 1861 Baltimore riot of 1861

Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. Friday Apr 19, 1861 As States sent Union regiments south, on April 19, Baltimore mobs in control of the rail links attacked Union troops who were changing trains. Local leaders' groups later burned critical rail bridges to the capital and the Army responded by arresting local Maryland officials. Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus where needed for the security of troops trying to reach Washington. John Merryman, one Maryland official hindering the U.S. troop movements, petitioned Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney to issue a writ of habeas corpus. In June Taney, ruling only for the lower circuit court in ex parte Merryman, issued the writ which he felt could only be suspended by Congress. Lincoln persisted with the policy of suspension in select areas.

Illinois, U.S. 1861 Lincoln professed to friends in 1861 to be "an old line Whig, a disciple of Henry Clay"

Illinois, U.S. 1861 True to his record, Lincoln professed to friends in 1861 to be "an old line Whig, a disciple of Henry Clay". Their party favored economic modernization in banking, tariffs to fund internal improvements including railroads, and urbanization.

U.S. 1861 Trent Affair

U.S. 1861 In the 1861 Trent Affair which threatened war with Great Britain, the U.S. Navy illegally intercepted a British mail ship, the Trent, on the high seas and seized two Confederate envoys; Britain protested vehemently while the U.S. cheered. Lincoln ended the crisis by releasing the two diplomats. Biographer James G. Randall dissected Lincoln's successful techniques: his restraint, his avoidance of any outward expression of truculence, his early softening of State Department's attitude toward Britain, his deference toward Seward and Sumner, his withholding of his paper prepared for the occasion, his readiness to arbitrate, his golden silence in addressing Congress, his shrewdness in recognizing that war must be averted, and his clear perception that a point could be clinched for America's true position at the same time that satisfaction was given to a friendly country.

Fairfax County and Prince William County, Virginia, U.S. Sunday Jul 21, 1861 U.S. Tuesday Aug 6, 1861 Lincoln signed the Confiscation Act

U.S. Tuesday Aug 6, 1861 On August 6, 1861, Lincoln signed the Confiscation Act that authorized judicial proceedings to confiscate and free slaves who were used to support the Confederates. The law had little practical effect, but it signaled political support for abolishing slavery.

U.S. Aug, 1861 John C. Frémont issued a martial edict freeing slaves of the rebels

U.S. Aug, 1861 In August 1861, General John C. Frémont, the 1856 Republican presidential nominee, without consulting Washington, issued a martial edict freeing slaves of the rebels. Lincoln cancelled the illegal proclamation as politically motivated and lacking military necessity. As a result, Union enlistments from Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri increased by over 40,000.

Washington D.C., U.S. Jan, 1862 Lincoln replaced War Secretary Simon Cameron with Edwin Stanton

Washington D.C., U.S. Jan, 1862 Lincoln painstakingly monitored the telegraph reports coming into the War Department. He tracked all phases of the effort, consulting with governors, and selecting generals based on their success, their state, and their party. In January 1862, after complaints of inefficiency and profiteering in the War Department, Lincoln replaced War Secretary Simon Cameron with Edwin Stanton. Stanton centralized the War Department's activities, auditing and canceling contracts, saving the federal government $17,000,000.

U.S. Tuesday Mar 11, 1862 U.S. May, 1862 U.S. Jun, 1862 1862 midterm elections

U.S. Jun, 1862 McClellan then resisted the president's demand that he pursue Lee's withdrawing army, while General Don Carlos Buell likewise refused orders to move the Army of the Ohio against rebel forces in eastern Tennessee. Lincoln replaced Buell with William Rosecrans; and after the 1862 midterm elections he replaced McClellan with Ambrose Burnside. The appointments were both politically neutral and adroit on Lincoln's part.

Washington D.C., U.S. Jun, 1862 U.S. Thursday Jul 17, 1862 Minnesota, Dakota Territory Sunday Aug 17, 1862 U.S. Friday Aug 22, 1862 A wish

U.S. Friday Aug 22, 1862 Privately, Lincoln concluded that the Confederacy's slave base had to be eliminated. Copperheads argued that emancipation was a stumbling block to peace and reunification; Republican editor Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune agreed. In a letter of August 22, 1862, Lincoln said that while he personally wished all men could be free, regardless of that, his first obligation as president was to preserve the Union: My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union ... I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.

Prince William County, Virginia, U.S. Friday Aug 29, 1862 Second Battle of Bull Run

Prince William County, Virginia, U.S. Friday Aug 29, 1862 Pope was then soundly defeated at the Second Battle of Bull Run in the summer of 1862, forcing the Army of the Potomac back to defend Washington. Despite his dissatisfaction with McClellan's failure to reinforce Pope, Lincoln restored him to command of all forces around Washington.

Washington County, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, U.S. Wednesday Sep 17, 1862 Battle of Antietam

Washington County, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, U.S. Wednesday Sep 17, 1862 General Robert E. Lee's forces crossed the Potomac River into Maryland, leading to the Battle of Antietam. That battle, a Union victory, was among the bloodiest in American history; it facilitated Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in January.

Spotsylvania County and Fredericksburg, Virginia, U.S. Thursday Dec 11, 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg

Spotsylvania County and Fredericksburg, Virginia, U.S. Thursday Dec 11, 1862 Burnside, against presidential advice, launched an offensive across the Rappahannock River and was defeated by Lee at Fredericksburg in December. Desertions during 1863 came in the thousands and only increased after Fredericksburg, so Lincoln replaced Burnside with Joseph Hooker.

U.S. Thursday Jan 1, 1863 Tennessee, U.S. 1863 Recruit black troops in more than token numbers

Tennessee, U.S. 1863 Enlisting former slaves became official policy. By the spring of 1863, Lincoln was ready to recruit black troops in more than token numbers. In a letter to Tennessee military governor Andrew Johnson encouraging him to lead the way in raising black troops, Lincoln wrote, "The bare sight of 50,000 armed and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi would end the rebellion at once".

Spotsylvania County, Virginia, U.S. Thursday Apr 30, 1863 Battle of Chancellorsville

Spotsylvania County, Virginia, U.S. Thursday Apr 30, 1863 Hooker was routed by Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May, then resigned and was replaced by George Meade. Meade followed Lee north into Pennsylvania and beat him in the Gettysburg Campaign, but then failed to follow up despite Lincoln's demands. At the same time, Grant captured Vicksburg and gained control of the Mississippi River, splitting the far western rebel states.

West Virginia, U.S. Saturday Jun 20, 1863 U.S. 1863 Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, U.S. Wednesday Nov 18, 1863 Lincoln spoke at the dedication of the Gettysburg battlefield cemetery

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, U.S. Wednesday Nov 18, 1863 Lincoln spoke at the dedication of the Gettysburg battlefield cemetery on November 19, 1863. In 272 words, and three minutes, Lincoln asserted that the nation was born not in 1789, but in 1776, "conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal". He defined the war as dedicated to the principles of liberty and equality for all. He declared that the deaths of so many brave soldiers would not be in vain, that slavery would end, and the future of democracy would be assured, that "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth". Defying his prediction that "the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here", the Address became the most quoted speech in American history.

Washington D.C., U.S. Tuesday Dec 8, 1863 Washington D.C., U.S. Wednesday Mar 2, 1864 Lincoln promoted Grant to Lieutenant General

Washington D.C., U.S. Wednesday Mar 2, 1864 Lincoln was concerned that Grant might be considering a presidential candidacy in 1864. He arranged for an intermediary to inquire into Grant's political intentions, and once assured that he had none, Lincoln promoted Grant to the newly revived rank of Lieutenant General, a rank which had been unoccupied since George Washington. Authorization for such a promotion "with the advice and consent of the Senate" was provided by a new bill which Lincoln signed the same day he submitted Grant's name to the Senate. His nomination was confirmed by the Senate on March 2, 1864.

Virginia, U.S. Wednesday May 4, 1864 U.S. 1864 Lincoln would still defeat the Confederacy before turning over the White House

U.S. 1864 Grant's bloody stalemates damaged Lincoln's re-election prospects, and many Republicans feared defeat. Lincoln confidentially pledged in writing that if he should lose the election, he would still defeat the Confederacy before turning over the White House; Lincoln did not show the pledge to his cabinet, but asked them to sign the sealed envelope. The pledge read as follows: "This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterward."

Nevada, U.S. Monday Oct 31, 1864 U.S. Tuesday Nov 8, 1864 Washington D.C., U.S. 1864 Lincoln ran for reelection in 1864

Washington D.C., U.S. 1864 Lincoln ran for reelection in 1864, while uniting the main Republican factions, along with War Democrats Edwin M. Stanton and Andrew Johnson. Lincoln used conversation and his patronage powers—greatly expanded from peacetime—to build support and fend off the Radicals' efforts to replace him. At its convention, the Republicans selected Johnson as his running mate. To broaden his coalition to include War Democrats as well as Republicans, Lincoln ran under the label of the new Union Party.

Washington D.C., U.S. Saturday Mar 4, 1865 Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address

Washington D.C., U.S. Saturday Mar 4, 1865 On March 4, 1865, Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address. In it, he deemed the war casualties to be God's will. Lincoln said: Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man's 250 years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said 3,000 years ago, so still it must be said, "the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether". With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Petersburg, Virginia, U.S. Saturday Apr 1, 1865 Grant nearly encircled Petersburg in a siege

Petersburg, Virginia, U.S. Saturday Apr 1, 1865 As Grant continued to weaken Lee's forces, efforts to discuss peace began. Confederate Vice President Stephens led a group meeting with Lincoln, Seward, and others at Hampton Roads. Lincoln refused to negotiate with the Confederacy as a coequal; his objective to end the fighting was not realized. On April 1, 1865, Grant nearly encircled Petersburg in a siege. The Confederate government evacuated Richmond and Lincoln visited the conquered capital. On April 9, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox, officially ending the war.

Appomattox, Virginia, U.S. Saturday Apr 8, 1865 Ford's Theatre, Washington D.C., U.S. Saturday Apr 15, 1865 Booth's shot

Ford's Theatre, Washington D.C., U.S. Saturday Apr 15, 1865 12:19:00 AM At 10:14 pm, John Wilkes Booth entered the back of Lincoln's theater box, crept up from behind, and fired at the back of Lincoln's head, mortally wounding him. Lincoln's guest Major Henry Rathbone momentarily grappled with Booth, but Booth stabbed him and escaped.

Petersen House, Washington D.C., U.S. Saturday Apr 15, 1865 Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield, Illinois, U.S. Friday Apr 21, 1865 Funeral

Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield, Illinois, U.S. Friday Apr 21, 1865 The late President lay in state, first in the East Room of the White House, and then in the Capitol Rotunda from April 19 through April 21. The caskets containing Lincoln's body and the body of his son Willie traveled for three weeks on the Lincoln Special funeral train. The train followed a circuitous route from Washington D.C. to Springfield, Illinois, stopping at many cities for memorials attended by hundreds of thousands.

Virginia, U.S. Wednesday Apr 26, 1865 U.S. Wednesday Dec 6, 1865 Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

U.S. Wednesday Dec 6, 1865 After implementing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln increased pressure on Congress to outlaw slavery throughout the nation with a constitutional amendment. He declared that such an amendment would "clinch the whole matter" and by December 1863 an amendment was brought to Congress. This first attempt fell short of the required two-thirds majority in the House of Representatives. Passage became part of the Republican/Unionist platform, and after a House debate the second attempt passed on January 31, 1865. With ratification, it became the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution on December 6, 1865.