History of Roman Empire

27 BC to 395

Rome, Mediterranean Sea in Europe, Northern Africa, and Western Asia

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterranean Sea in Europe, Northern Africa, and Western Asia ruled by emperors.

Osnabrück County, Lower Saxony (Present-Day in Germany) Sep, 9 Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

Osnabrück County, Lower Saxony (Present-Day in Germany) Sep, 9 The Illyrian tribes revolted and had to be crushed, and three full legions under the command of Publius Quinctilius Varus were ambushed and destroyed at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in AD 9 by Germanic tribes led by Arminius.

Rome 13 Nola (Present-Day in Naples, Italy) Tuesday Aug 19, 14 Rome Wednesday Sep 17, 14 Tiberius's reign

Rome Wednesday Sep 17, 14 The early years of Tiberius's reign were relatively peaceful. Tiberius secured the overall power of Rome and enriched its treasury. However, his rule soon became characterized by paranoia. He began a series of treason trials and executions, which continued until his death in 37.

Capri, Italy 26 Tiberius left power in the hands of Lucius Aelius Sejanus

Capri, Italy 26 He left power in the hands of the commander of the guard, Lucius Aelius Sejanus. Tiberius himself retired to live at his villa on the island of Capri in 26, leaving the administration in the hands of Sejanus, who carried on the persecutions with contentment.

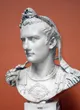

Roman Empire 31 Miseno, Italy, Roman Empire Monday Mar 16, 37 Roman Empire Monday Mar 16, 37 Roman Empire 37 Caligula's Illness

Roman Empire 37 The Caligula that emerged in late 37 demonstrated features of mental instability that led modern commentators to diagnose him with such illnesses as encephalitis, which can cause mental derangement, hyperthyroidism, or even a nervous breakdown (perhaps brought on by the stress of his position).

Palatine Hill, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Thursday Jan 24, 41 Caligula was assassinated

Palatine Hill, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Thursday Jan 24, 41 In 41, Caligula was assassinated by the commander of the guard Cassius Chaerea. Also killed were his fourth wife Caesonia and their daughter Julia Drusilla. For two days following his assassination, the senate debated the merits of restoring the Republic.

Rome Thursday Jan 24, 41 Claudius

Rome Thursday Jan 24, 41 Claudius was a younger brother of Germanicus and had long been considered a weakling and a fool by the rest of his family. The Praetorian Guard, however, acclaimed him as emperor. Claudius was neither paranoid like his uncle Tiberius, nor insane like his nephew Caligula, and was, therefore, able to administer the Empire with reasonable ability.

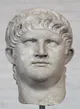

United Kingdom 43 Gardens of Lucullus, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire 48 Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Tuesday Oct 13, 54 Rome Tuesday Oct 13, 54 Italy, Roman Empire (Probably in Misenum, Italy) 59 Rome Friday Jul 18, 64 Great Fire of Rome

Rome Friday Jul 18, 64 He believed himself a god and decided to build an opulent palace for himself. The so-called Domus Aurea, meaning golden house in Latin, was constructed atop the burnt remains of Rome after the Great Fire of Rome (64). Nero was ultimately responsible for the fire. By this time Nero was hugely unpopular despite his attempts to blame the Christians for most of his regime's problems.

Rome Friday Jun 8, 68 Servius Sulpicius Galba

Rome Friday Jun 8, 68 Servius Sulpicius Galba, born as Lucius Livius Ocella Sulpicius Galba, was a Roman emperor who ruled from AD 68 to 69. He was the first emperor in the Year of the Four Emperors and assumed the position following Emperor Nero's suicide. Galba's physical weakness and general apathy led to him being selected over by favorites. Unable to gain popularity with the people or maintain the support of the Praetorian Guard, Galba was murdered by Otho, who became emperor in his place.

Outside Rome Saturday Jun 9, 68 Rome Tuesday Jan 15, 69 Marcus Otho

Rome Tuesday Jan 15, 69 Marcus Otho was Roman emperor for three months, from 15 January to 16 April 69. He was the second emperor of the Year of the Four Emperors. Inheriting the problem of the rebellion of Vitellius, commander of the army in Germania Inferior, Otho led a sizeable force that met Vitellius' army at the Battle of Bedriacum. After initial fighting resulted in 40,000 casualties, and a retreat of his forces, Otho committed suicide rather than fight on, and Vitellius was proclaimed emperor.

Rome Friday Apr 19, 69 Aulus Vitellius

Rome Friday Apr 19, 69 Aulus Vitellius was Roman Emperor for eight months, from 19 April to 20 December AD 69. Vitellius was proclaimed emperor following the quick succession of the previous emperors Galba and Otho, in a year of civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors. His claim to the throne was soon challenged by legions stationed in the eastern provinces, who proclaimed their commander Vespasian emperor instead. War ensued, leading to a crushing defeat for Vitellius at the Second Battle of Bedriacum in northern Italy. Once he realized his support was wavering, Vitellius prepared to abdicate in favor of Vespasian. He was not allowed to do so by his supporters, resulting in a brutal battle for Rome between Vitellius' forces and the armies of Vespasian. He was executed in Rome by Vespasian's soldiers on 20 December 69.

Rome Monday Jul 1, 69 Batavia (Present-Day in Netherlands) 69 Revolt of the Batavi

Batavia (Present-Day in Netherlands) 69 The Revolt of the Batavi took place in the Roman province of Germania Inferior between AD 69 and 70. It was an uprising against the Roman Empire started by the Batavi, a small but militarily powerful Germanic tribe that inhabited Batavia, on the delta of the river Rhine. They were soon joined by the Celtic tribes from Gallia Belgica and some Germanic tribes.

Rome 69 Rome Saturday Jun 24, 79 Pompeii, Italy, Roman Empire 79 Rome Sunday Sep 14, 81 Moesia, Dacia 86 Rome Tuesday Sep 18, 96 Nerva

Rome Tuesday Sep 18, 96 On 18 September 96, Domitian was assassinated in a palace conspiracy involving members of the Praetorian Guard and several of his freedmen. On the same day, Nerva was declared emperor by the Roman Senate. As the new ruler of the Roman Empire, he vowed to restore liberties that had been curtailed during the autocratic government of Domitian.

Rome 97 Nerva adopted Trajan

Rome 97 Nerva's brief reign was marred by financial difficulties and his inability to assert his authority over the Roman army. A revolt by the Praetorian Guard in October 97 essentially forced him to adopt an heir. After some deliberation, Nerva adopted Trajan, a young and popular general, as his successor.

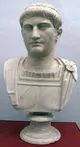

Gardens of Sallust, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Monday Jan 27, 98 Transylvania, Romania Sep, 101 Second Battle of Tapae

Transylvania, Romania Sep, 101 Upon his accession to the throne, Trajan prepared and launched a carefully planned military invasion in Dacia, a region north of the lower Danube whose inhabitants the Dacians had long been an opponent to Rome. In 101, Trajan personally crossed the Danube and defeated the armies of the Dacian king Decebalus at the Battle of Tapae.

Sarmizegetusa Regia (Present-Day in Grădiștea de Munte, Hunedoara County, Romania) 105 Trajan invaded Sarmizegetusa Regia

Sarmizegetusa Regia (Present-Day in Grădiștea de Munte, Hunedoara County, Romania) 105 Decebalus complied with the terms for a time, but before long he began inciting revolt. In 105 Trajan once again invaded and after a yearlong invasion ultimately defeated the Dacians by conquering their capital, Sarmizegetusa Regia. King Decebalus, cornered by the Roman cavalry, eventually committed suicide rather than being captured and humiliated in Rome.

Rome 105 Artaxata, Kingdom of Armenia (Present-Day Artashat, Armenia) 112 Armenia 110s Ctesiphon (Present-Day in Iraq) 116 Susa (Present-Day Shush, Khuzestan Province, Iran) 116 Roman Empire 117 Roman Empire (most-probablyin Turkey) 117 Hadrian as heir

Roman Empire (most-probablyin Turkey) 117 Failure to nominate an heir could invite chaotic, destructive wresting of power by a succession of competing claimants – a civil war. Too early a nomination could be seen as an abdication, and reduce the chance for an orderly transmission of power. As Trajan lay dying, nursed by his wife, Plotina, and closely watched by Perfect Attianus, he could have lawfully adopted Hadrian as heir, by means of a simple deathbed wish, expressed before witnesses; but when an adoption document was eventually presented, it was signed not by Trajan but by Plotina, and was dated the day after Trajan's death.

Selinus, Cilicia (Present-Day in Turkey) Wednesday Aug 11, 117 Trajan died

Selinus, Cilicia (Present-Day in Turkey) Wednesday Aug 11, 117 Early in 117, Trajan grew ill and set out to sail back to Italy. His health declined throughout the spring and summer of 117, something publicly acknowledged by the fact that a bronze bust displayed at the time in the public baths of Ancyra showed him clearly aged and emaciated. After reaching Selinus (modern Gazipaşa) in Cilicia, which was afterward called Trajanopolis, he suddenly died from edema, probably on 11 August.

Roman Empire Wednesday Aug 11, 117 Roman Empire 117 Four executions

Roman Empire 117 Hadrian relieved Judea's governor, the outstanding Moorish general Lusius Quietus, of his personal guard of Moorish auxiliaries; then he moved on to quell disturbances along the Danube frontier. There was no public trial for the four – they were tried in absentia, hunted down, and killed. Hadrian claimed that Attianus had acted on his own initiative, and rewarded him with senatorial status and consular rank; then pensioned him off, no later than 120. Hadrian assured the senate that henceforth their ancient right to prosecute and judge their own would be respected. In Rome, Hadrian's former guardian and current Praetorian Prefect, Attianus, claimed to have uncovered a conspiracy involving Lusius Quietus and three other leading senators, Lucius Publilius Celsus, Aulus Cornelius Palma Frontonianus, and Gaius Avidius Nigrinus.

United Kingdom 119 Major rebellion in Britannia

United Kingdom 119 Prior to Hadrian's arrival in Britannia, the province had suffered a major rebellion, from 119 to 121. Inscriptions tell of an expeditio Britannica that involved major troop movements, including the dispatch of a detachment (vexillatio), comprising some 3,000 soldiers. Fronto writes about military losses in Britannia at the time.

Roman Empire 120 Parthian Empire 121 United Kingdom 122 Hadrian had concluded his visit to Britannia

United Kingdom 122 A shrine was erected in York to Britannia as the divine personification of Britain; coins were struck, bearing her image, identified as BRITANNIA. By the end of 122, Hadrian had concluded his visit to Britannia. He never saw the finished wall that bears his name.

United Kingdom 122 Hadrian's Wall

United Kingdom 122 Coin legends of 119–120 attest that Quintus Pompeius Falco was sent to restore order. In 122 Hadrian initiated the construction of a wall, "to separate Romans from barbarians". The idea that the wall was built in order to deal with an actual threat or its resurgence, however, is probable but nevertheless conjectural.

Mauretania or "Ancient Maghreb" 123 Hadrian crossed the Mediterranean to Mauretania

Mauretania or "Ancient Maghreb" 123 In 123, Hadrian crossed the Mediterranean to Mauretania, where he personally led a minor campaign against local rebels. The visit was cut short by reports of war preparations by Parthia; Hadrian quickly headed eastwards. At some point, he visited Cyrene, where he personally funded the training of young men from well-bred families for the Roman military. Cyrene had benefited earlier (in 119) from his restoration of public buildings destroyed during the earlier Jewish revolt.

Roman Empire 125 Western Asia 134 Antoninus Pius as proconsul of Asia

Western Asia 134 Antoninus Pius was next appointed by Emperor Hadrian as one of the four proconsuls to administer Italia, his district including Etruria, where he had estates. He then greatly increased his reputation by his conduct as proconsul of Asia, probably during 134–135.

Judea Province 136 Roman Empire Tuesday Feb 25, 138 Antoninus Pius "adopted son"

Roman Empire Tuesday Feb 25, 138 Antoninus Pius acquired much favor with Hadrian, who adopted him as his son and successor on 25 February 138, after the death of his first adopted son Lucius Aelius, on the condition that Antoninus would, in turn, adopt Marcus Annius Verus, the son of his wife's brother, and Lucius, son of Lucius Aelius, who afterward became the emperors, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Baiae, Italy, Roman Empire (Present-Day Bacoli, Campania, Italy) Thursday Jul 10, 138 Roman Empire Friday Jul 11, 138 Roman Empire 140 United Kingdom 142 Construction began of Antonine Wall

United Kingdom 142 It was however in Britain that Antoninus decided to follow a new, more aggressive path, with the appointment of a new governor in 139, Quintus Lollius Urbicus, a native of Numidia and previously governor of Germania Inferior as well as a new man. Under instructions from the emperor, Lollius undertook an invasion of southern Scotland, winning some significant victories, and constructing the Antonine Wall from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde. The wall, however, was soon gradually decommissioned during the mid-150s and eventually abandoned late during the reign (early 160s), for reasons that are still not quite clear.

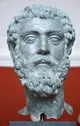

Lorium, Etruria, Italy, Roman Empire Saturday Mar 7, 161 Rome Saturday Mar 7, 161 Marcus Aurelius

Rome Saturday Mar 7, 161 Marcus was effectively the sole ruler of the Empire. The formalities of the position would follow. The senate would soon grant him the name Augustus and the title imperator, and he would soon be formally elected as Pontifex Maximus, chief priest of the official cults. Marcus made some show of resistance: the biographer writes that he was 'compelled' to take imperial power.

Roman Empire 161 Daqin (Present-Day in China) 166 Roman embassy from "Daqin"

Daqin (Present-Day in China) 166 It is possible that an alleged Roman embassy from "Daqin" that arrived in Eastern Han China in 166 via a Roman maritime route into the South China Sea, landing at Jiaozhou (northern Vietnam) and bearing gifts for the Emperor Huan of Han (r. 146–168), was sent by Marcus Aurelius, or his predecessor Antoninus Pius (the confusion stems from the transliteration of their names as "Andun", Chinese: 安敦).

Altinum, Italy, Roman Empire 169 Lucius Verus died

Altinum, Italy, Roman Empire 169 In the spring of 168 war broke out on the Danubian border when the Marcomanni invaded the Roman territory. This war would last until 180, but Verus did not see the end of it. In 168, as Verus and Marcus Aurelius returned to Rome from the field, Verus fell ill with symptoms attributed to food poisoning, dying after a few days (169).

Roman Empire 179 Sirmium, Pannonia (Present-Day Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia) Friday Mar 17, 180 Rome, Roman Empire 182 Assassination attempt (Commodus)

Rome, Roman Empire 182 The first crisis of the reign came in 182 when Lucilla engineered a conspiracy against her brother. Her motive is alleged to have been the envy of Empress Crispina. Her husband, Pompeianus, was not involved, but two men alleged to have been her lovers, Marcus Ummidius Quadratus Annianus (the consul of 167, who was also her first cousin) and Appius Claudius Quintianus, attempted to murder Commodus as he entered a theater. They bungled the job and were seized by the emperor's bodyguard.

Rome, Roman Empire Monday Dec 31, 192 Rome, Roman Empire Thursday Mar 28, 193 Pertinax died

Rome, Roman Empire Thursday Mar 28, 193 On 28 March 193, Pertinax was at his palace when a contingent of some three hundred soldiers of the Praetorian Guard rushed the gates (two hundred according to Cassius Dio). Sources suggest that they had received only half their promised pay. Neither the guards on duty nor the palace officials chose to resist them. Pertinax sent Laetus to meet them, but he chose to side with the insurgents instead and deserted the emperor.

Rome 193 Throne was to be sold

Rome 193 After the murder of Pertinax on 28 March 193, the Praetorian guard announced that the throne was to be sold to the man who would pay the highest price. Titus Flavius Claudius Sulpicianus, prefect of Rome and Pertinax's father-in-law, who was in the Praetorian camp ostensibly to calm the troops, began making offers for the throne. Meanwhile, Julianus also arrived at the camp, and since his entrance was barred, shouted out offers to the guard. After hours of bidding, Sulpicianus promised 20,000 sesterces to every soldier; Julianus, fearing that Sulpicianus would gain the throne, then offered 25,000. The guards closed with the offer of Julianus, threw open the gates, and proclaimed him emperor. Threatened by the military, the senate also declared him emperor. His wife and his daughter both received the title Augusta.

Rome Thursday Mar 28, 193 Didius Julianus

Rome Thursday Mar 28, 193 Because Julianus bought his position rather than acquiring it conventionally through succession or conquest, he was a deeply unpopular emperor. When Julianus appeared in public, he frequently was greeted with groans and shouts of "robber and parricide." Once, a mob even obstructed his progress to the Capitol by pelting him with large stones.

Pannonia Tuesday Apr 9, 193 Septimius Severus proclaimed himself emperor

Pannonia Tuesday Apr 9, 193 Proclaimed emperor in 193 by his legionaries in Noricum during the political unrest that followed the death of Commodus, he secured sole rule over the empire in 197 after defeating his last rival, Clodius Albinus, at the Battle of Lugdunum. In securing his position as emperor, he founded the Severan dynasty.

Rome Sunday Jun 2, 193 Eboracum, Roman Empire (Present-Day in York, England, United Kingdom) Monday Feb 4, 211 Septimius Severus died

Eboracum, Roman Empire (Present-Day in York, England, United Kingdom) Monday Feb 4, 211 Severus is famously said to have given the advice to his sons: "Be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, scorn all others" before he died on 4 February 211. On his death, Severus was deified by the Senate and succeeded by his sons, Caracalla and Geta, who were advised by his wife Julia Domna. Severus was buried in the Mausoleum of Hadrian in Rome. His remains are now lost.

Rome Tuesday Dec 17, 211 Caracalla tried unsuccessfully to murder Geta

Rome Tuesday Dec 17, 211 The current stability of their joint government was only through the mediation and leadership of their mother, Julia Domna, accompanied by other senior courtiers and generals in the military. The historian Herodian asserted that the brothers decided to split the empire into two halves, but with the strong opposition of their mother, the idea was rejected, when, by the end of 211, the situation had become unbearable. Caracalla tried unsuccessfully to murder Geta during the festival of Saturnalia (17 December).

Rome Thursday Dec 26, 211 between Edessa and Carrhae (Present-Day in Turkey) Tuesday Apr 8, 217 Rome Friday Apr 11, 217 Macrinus was declared augustus

Rome Friday Apr 11, 217 On April 8, 217, Caracalla was assassinated traveling to Carrhae. Three days later, Macrinus was declared Augustus. Diadumenian was the son of Macrinus, born in 208. He was given the title Caesar in 217, when his father became augustus, and raised to co-Augustus the following year.

Cappadocia (Present-Day in Turkey) Monday Jun 8, 218 Macrinus died

Cappadocia (Present-Day in Turkey) Monday Jun 8, 218 However, his downfall was his refusal to award the pay and privileges promised to the eastern troops by Caracalla. He also kept those forces wintered in Syria, where they became attracted to the young Elagabalus. After months of mild rebellion by the bulk of the army in Syria, Macrinus took his loyal troops to meet the army of Elagabalus near Antioch. Despite a good fight by the Praetorian Guard, his soldiers were defeated. Macrinus managed to escape to Chalcedon but his authority was lost: he was betrayed and executed after a short reign of just 14 months. After his father's defeat outside Antioch, Diadumenian tried to escape east to Parthia, but was captured and killed.

Emesa (Present-Day Homs, Syria) Jun, 218 Rome Wednesday Mar 6, 222 A romur

Rome Wednesday Mar 6, 222 Alexander Severus was adopted as son and caesar by his slightly older and very unpopular cousin, the emperor Elagabalus at the urging of the influential and powerful Julia Maesa — who was the grandmother of both cousins and who had arranged for the emperor's acclamation by the Third Legion. On March 6, 222, when Alexander was just fourteen, a rumor went around the city troops that Alexander had been killed, triggering a revolt of the guards that had sworn his safety from Elegabalus and his accession as emperor.

Rome Wednesday Mar 13, 222 Severus Alexander

Rome Wednesday Mar 13, 222 The running of the Empire during this time was mainly left to his grandmother and mother (Julia Soaemias). Seeing that her grandson's outrageous behavior could mean the loss of power, Julia Maesa persuaded Elagabalus to accept his cousin Alexander Severus as caesar (and thus the nominal emperor-to-be). However, Alexander was popular with the troops, who viewed their new emperor with dislike: when Elagabalus, jealous of this popularity, removed the title of caesar from his nephew, the enraged Praetorian Guard swore to protect him. Elagabalus and his mother were murdered in a Praetorian Guard camp mutiny.

Moguntiacum, Germania Superior (Present-Day Mainz, Germany) Thursday Mar 19, 235 Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander died

Moguntiacum, Germania Superior (Present-Day Mainz, Germany) Thursday Mar 19, 235 His prosecution of the war against a German invasion of Gaul led to his overthrow by the troops he was leading, whose regard the twenty-seven-year-old had lost during the campaign. Alexander was forced to face his German enemies in the early months of 235. By the time he and his mother arrived, the situation had settled, and so his mother convinced him that to avoid violence, trying to bribe the German army to surrender was the more sensible course of action. According to historians, it was this tactic combined with insubordination from his own men that destroyed his reputation and popularity. Alexander was thus assassinated together with his mother in a mutiny of the Legio XXII Primigenia at Moguntiacum (Mainz) while at a meeting with his generals. These assassinations secured the throne for Maximinus. He died after a rule of 13 years.

Rome Sunday Mar 22, 235 Rome Mar, 238 Gordian I proclaim himself emperor

Rome Mar, 238 Some young aristocrats in Africa murdered the imperial tax-collector then approached the regional governor, Gordian, and insisted that he proclaim himself emperor. Gordian agreed reluctantly, but as he was almost 80 years old, he decided to make his son joint emperor, with equal power. The Senate recognized father and son as emperors Gordian I and Gordian II, respectively. Their reign, however, lasted for only 20 days. Capelianus, the governor of the neighboring province of Numidia, held a grudge against the Gordians. He led an army to fight them and defeated them decisively at Carthage. Gordian II was killed in the battle, and on hearing this news, Gordian I hanged himself. Gordian I and II were deified by the senate.

Carthage, Africa Proconsularis (Present-Day in Tunisia) Thursday Apr 12, 238 Rome Sunday Apr 22, 238 Pupienus and Balbinus joint emperors

Rome Sunday Apr 22, 238 Meanwhile, Maximinus, now declared a public enemy, had already begun to march on Rome with another army. The senate's previous candidates, the Gordians, had failed to defeat him, and knowing that they stood to die if he succeeded, the senate needed a new emperor to defeat him. With no other candidates in view, on 22 April 238, they elected two elderly senators, Pupienus and Balbinus (who had both been part of a special senatorial commission to deal with Maximinus), as joint emperors. Therefore, Marcus Antonius Gordianus Pius, the thirteen-year-old grandson of Gordian I, was nominated as emperor Gordian III, holding power only nominally in order to appease the population of the capital, which was still loyal to the Gordian family.

Aquileia, Italy, Roman Empire Thursday May 10, 238 Rome Sunday Jul 29, 238 Gordian III was proclaimed sole emperor

Rome Sunday Jul 29, 238 The situation for Pupienus and Balbinus, despite Maximinus' death, was doomed from the start with popular riots, military discontent and enormous fire that consumed Rome in June 238. On July 29, Pupienus and Balbinus were killed by the Praetorian Guard and Gordian was proclaimed sole emperor.

Mesopotamia (Present-Day in Iraq) Sunday Feb 11, 244 Gordian III died

Mesopotamia (Present-Day in Iraq) Sunday Feb 11, 244 Gaius Julius Priscus and, later on, his own brother Marcus Julius Philippus, also known as Philip the Arab, stepped in at this moment as the new Praetorian Prefects Gordian would then start a second campaign. Around February 244, the Sasanians fought back fiercely to halt the Roman advance to Ctesiphon. The eventual fate of Gordian after the battle is unclear. Sasanian sources claim that a battle occurred (Battle of Misiche) near modern Fallujah (Iraq) and resulted in a major Roman defeat and the death of Gordian III.

Rome Feb, 244 Dacia 246 Carpicus Maximus

Dacia 246 The Carpi moved through Dacia, crossed the Danube, and emerged in Moesia where they threatened the Balkans. Establishing his headquarters in Philippopolis in Thrace, he pushed the Carpi across the Danube and chased them back into Dacia, so that by the summer of 246, he claimed victory against them, along with the title "Carpicus Maximus".

Moesia Sep, 249 Decius was proclaimed emperor

Moesia Sep, 249 Overwhelmed by the number of invasions and usurpers, Philip offered to resign, but the Senate decided to throw its support behind the emperor, with a certain Gaius Messius Quintus Decius most vocal of all the senators. Philip was so impressed by his support that he dispatched Decius to the region with a special command encompassing all of the Pannonian and Moesian provinces. This had a dual purpose of both quelling the rebellion of Pacatianus as well as dealing with the barbarian incursions. Although Decius managed to quell the revolt, discontent in the legions was growing. Decius was proclaimed emperor by the Danubian armies in the spring of 249 and immediately marched on Rome.

Verona, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 249 Philip was killed

Verona, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 249 Although Decius tried to come to terms with Philip, Philip's army met the usurper near modern Verona that summer. Decius easily won the battle and Philip was killed sometime in September 249, either in the fighting or assassinated by his own soldiers who were eager to please the new ruler. Philip's eleven-year-old son and heir may have been killed with his father and Priscus disappeared without a trace.

Abritus, Moesia (Present-Day Razgrad, Bulgaria) 251 Decius was killed

Abritus, Moesia (Present-Day Razgrad, Bulgaria) 251 Battle of Abritus was fought between the Romans and a federation of Gothic and Scythian tribesmen under the Gothic king Cniva. The Roman army of three legions was soundly defeated, and Roman emperors Decius and his son Herennius Etruscus were both killed in battle.

Rome Jun, 251 Trebonianus Gallus

Rome Jun, 251 In June 251, Decius and his co-emperor and son Herennius Etruscus died in the Battle of Abrittus at the hands of the Goths they were supposed to punish for raids into the empire. According to rumors supported by Dexippus (a contemporary Greek historian) and the thirteenth Sibylline Oracle, Decius' failure was largely owing to Gallus, who had conspired with the invaders. In any case, when the army heard the news, the soldiers proclaimed Gallus emperor, despite Hostilian, Decius' surviving son, ascending the imperial throne in Rome. This action of the army, and the fact that Gallus seems to have been on good terms with Decius' family, makes Dexippus' allegation improbable. Gallus did not back down from his intention to become emperor, but accepted Hostilian as co-emperor, perhaps to avoid the damage of another civil war.

Barbalissos, Syria (Present-Day Qalʿat al-Bālis, Syria) 252 Interamna (Present-Day Terni, Italy) Aug, 253 Gallus was killed

Interamna (Present-Day Terni, Italy) Aug, 253 Since the army was no longer pleased with the Emperor, the soldiers proclaimed Aemilianus emperor. With a usurper, supported by Pauloctus, threatening the throne, Gallus prepared for a fight. He recalled several legions and ordered reinforcements to return to Rome from Gaul under the command of the future emperor Publius Licinius Valerianus. Despite these dispositions, Aemilianus marched onto Italy ready to fight for his claim and caught Gallus at Interamna (modern Terni) before the arrival of Valerianus. What exactly happened is not clear. Later sources claim that after an initial defeat, Gallus and Volusianus were murdered by their own troops; or Gallus did not have the chance to face Aemilianus at all because his army went over to the usurper. In any case, both Gallus and Volusianus were killed in August 253.

Rome 253 Marcus Aemilius Aemilianus "Aemilian"

Rome 253 Aemilian continued towards Rome. The Roman senate, after a short opposition, decided to recognize him as emperor. According to some sources, Aemilian then wrote to the Senate, promising to fight for the Empire in Thrace and against Persia and to relinquish his power to the Senate, of which he considered himself a general.

Spoletium, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 253 Aemilian died

Spoletium, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 253 Valerian, governor of the Rhine provinces, was on his way south with an army which, according to Zosimus, had been called in as reinforcement by Gallus. But modern historians believe this army, possibly mobilized for an incumbent campaign in the East, moved only after Gallus' death to support Valerian's bid for power. Emperor Aemilian's men, fearful of civil war and Valerian's larger force, mutinied. They killed Aemilian at Spoletium or at the Sanguinarium bridge, between Oriculum and Narnia (halfway between Spoletium and Rome), and recognized Valerian as the new emperor.

Rome Saturday Oct 22, 253 Valerian's first act as emperor

Rome Saturday Oct 22, 253 Valerian's first act as emperor on October 22, 253, was to appoint his son Gallienus caesar. Early in his reign, affairs in Europe went from bad to worse, and the whole West fell into disorder. In the East, Antioch had fallen into the hands of a Sassanid vassal and Armenia was occupied by Shapur I (Sapor).

Moesia and Pannonia 253 Aemilianus defeated the invaders

Moesia and Pannonia 253 On the Danube, Scythian tribes were once again on the loose, despite the peace treaty signed in 251. They invaded Asia Minor by sea, burned the great Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, and returned home with the plunder. Lower Moesia was also invaded in early 253. Aemilianus, governor of Moesia Superior and Pannonia, took the initiative and defeated the invaders.

Danube region 256 Gallienus proclaimed his elder son Valerian II caesar

Danube region 256 During his Danube sojourn (Drinkwater suggests in 255 or 256), he proclaimed his elder son Valerian II caesar and thus official heir to himself and Valerian I; the boy probably joined Gallienus on the campaign at that time, and when Gallienus moved west to the Rhine provinces in 257, he remained behind on the Danube as the personification of Imperial authority.

Pannonia 258 Ingenuus

Pannonia 258 Sometime between 258 and 260 (the exact date is unclear), while Valerian was distracted with the ongoing invasion of Shapur I in the East, and Gallienus was preoccupied with his problems in the West, Ingenuus, governor of at least one of the Pannonian provinces, took advantage and declared himself emperor. Valerian II had apparently died on the Danube, most likely in 258. Ingenuus may have been responsible for Valerian II's death. Alternatively, the defeat and capture of Valerian at the battle of Edessa may have been the trigger for the subsequent revolts of Ingenuus, Regalianus, and Postumus.

Pannonia 250s Gallienus fast respond

Pannonia 250s In any case, Gallienus reacted with great speed. He left his son Saloninus as caesar at Cologne, under the supervision of Albanus (or Silvanus) and the military leadership of Postumus. He then hastily crossed the Balkans, taking with him the new cavalry corps (comitatus) under the command of Aureolus and defeated Ingenuus at Mursa or Sirmium. Ingenuus was killed by his own guards or committed suicide by drowning himself after the fall of his capital, Sirmium.

Edessa, Osroene (Present-Day in Turkey) 260 Battle of Edessa

Edessa, Osroene (Present-Day in Turkey) 260 In 254, 255, and 257, Valerian again became Consul Ordinarius. By 257, he had recovered Antioch and returned the province of Syria to Roman control. The following year, the Goths ravaged Asia Minor. In 259, Valerian moved on to Edessa, but an outbreak of plague killed a critical number of legionaries, weakening the Roman position, and the town was besieged by the Persians. At the beginning of 260, Valerian was decisively defeated in the Battle of Edessa and held prisoner for the remainder of his life. Valerian's capture was a tremendous defeat for the Romans.

Naissus (Present-Day Niš, Serbia) 268 Battle of Naissus

Naissus (Present-Day Niš, Serbia) 268 In the years 267–269, Goths and other barbarians invaded the empire in great numbers. Sources are extremely confused on the dating of these invasions, the participants, and their targets. Modern historians are not even able to discern with certainty whether there were two or more of these invasions or a single prolonged one. It seems that, at first, a major naval expedition was led by the Heruli starting from north of the Black Sea and leading to the ravaging of many cities of Greece (among them, Athens and Sparta). Then another, even more numerous army of invaders started a second naval invasion of the empire. The Romans defeated the barbarians on sea first. Gallienus' army then won a battle in Thrace, and the emperor pursued the invaders. According to some historians, he was the leader of the army who won the great Battle of Naissus, while the majority believes that the victory must be attributed to his successor, Claudius II.

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 268 Gallienus was challenged by Aureolus

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 268 In 268, at some time before or soon after the battle of Naissus, the authority of Gallienus was challenged by Aureolus, commander of the cavalry stationed in Mediolanum (Milan), who was supposed to keep an eye on Postumus. Instead, he acted as deputy to Postumus until the very last days of his revolt, when he seems to have claimed the throne for himself. The decisive battle took place at what is now Pontirolo Nuovo near Milan; Aureolus was clearly defeated and driven back to Milan. Gallienus laid siege to the city but was murdered during the siege. There are differing accounts of the murder, but the sources agree that most of Gallienus' officials wanted him dead.

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Sep, 268 Gallienus died

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Sep, 268 Cecropius, commander of the Dalmatians, spread the word that the forces of Aureolus were leaving the city, and Gallienus left his tent without his bodyguard, only to be struck down by Cecropius. According to Aurelius Victor and Zonaras, on hearing the news that Gallienus was dead, the Senate in Rome ordered the execution of his family (including his brother Valerianus and son Marinianus) and their supporters, just before receiving a message from Claudius to spare their lives and deify his predecessor.

Rome Sep, 268 Claudius Gothicus was chosen by the army

Rome Sep, 268 Whichever story is true, Gallienus was killed in the summer of 268, and Claudius was chosen by the army outside of Milan to succeed him. Accounts tell of people hearing the news of the new emperor and reacting by murdering Gallienus' family members until Claudius declared he would respect the memory of his predecessor. Claudius had the deceased emperor deified and buried in a family tomb on the Appian Way. The traitor Aureolus was not treated with the same reverence, as he was killed by his besiegers after a failed attempt to surrender.

Sirmium, Pannonia Inferior (Present-Day Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia) Jan, 270 Claudius Gothicus died

Sirmium, Pannonia Inferior (Present-Day Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia) Jan, 270 However, he fell victim to the Plague of Cyprian (possibly smallpox) and died early in January 270. Before his death, he is thought to have named Aurelian as his successor, though Claudius' brother Quintillus briefly seized power.

Rome 270 Quintillus

Rome 270 Quintillus was declared emperor either by the Senate or by his brother's soldiers upon the latter's death in 270. Eutropius reports Quintillus to have been elected by soldiers of the Roman army immediately following the death of his brother; the choice was reportedly approved by the Roman Senate.

Aquileia, Italy, Roman Empire 270 Sirmium May, 270 Aurelian was proclaimed emperor

Sirmium May, 270 When Claudius died, his brother Quintillus seized power with the support of the Senate. With an act typical of the Crisis of the Third Century, the army refused to recognize the new Emperor, preferring to support one of its own commanders: Aurelian was proclaimed emperor about May 270 by the legions in Sirmium.

Northern Italy 270 Aurelian campaigned in northern Italia

Northern Italy 270 The first actions of the new Emperor were aimed at strengthening his own position in his territories. Late in 270, Aurelian campaigned in northern Italia against the Vandals, Juthungi, and Sarmatians, expelling them from Roman territory. To celebrate these victories, Aurelian was granted the title of Germanicus Maximus.

Roman Empire 272 Aurelian turned his attention to the lost eastern provinces of the empire

Roman Empire 272 In 272, Aurelian turned his attention to the lost eastern provinces of the empire, the Palmyrene Empire, ruled by Queen Zenobia from the city of Palmyra. Zenobia had carved out her own empire, encompassing Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and large parts of Asia Minor. The Syrian queen cut off Rome's shipments of grain, and in a matter of weeks, the Romans started running low on bread. In the beginning, Aurelian had been recognized as Emperor, while Vaballathus, the son of Zenobia, held the title of rex and imperator ("king" and "supreme military commander"), but Aurelian decided to invade the eastern provinces as soon as he felt his army to be strong enough.

Rome 272 Aurelian is believed to have terminated Trajan's alimenta program

Rome 272 Aurelian is believed to have terminated Trajan's alimenta program. Roman prefect Titus Flavius Postumius Quietus was the last known official in charge of the alimenta, in 272 AD. If Aurelian "did suppress this food distribution system, he most likely intended to put into effect a more radical reform."

Tyana (Present-Day Kemerhisar, Niğde Province, Turkey) 272 Fall of Tyana

Tyana (Present-Day Kemerhisar, Niğde Province, Turkey) 272 Asia Minor was recovered easily; every city but Byzantium and Tyana surrendered to him with little resistance. The fall of Tyana lent itself to a legend: Aurelian to that point had destroyed every city that resisted him, but he spared Tyana after having a vision of the great 1st-century philosopher Apollonius of Tyana, whom he respected greatly, in a dream.

Palmyra (Present-Day Tadmur, Homs Governorate, Syria) 272 Fall of Palmyra

Palmyra (Present-Day Tadmur, Homs Governorate, Syria) 272 Within six months, his armies stood at the gates of Palmyra, which surrendered when Zenobia tried to flee to the Sassanid Empire. Eventually, Zenobia and her son were captured and made to walk on the streets of Rome in his triumph, the woman in golden chains. With the grain stores once again shipped to Rome, Aurelian's soldiers handed out free bread to the citizens of the city, and the Emperor was hailed a hero by his subjects. After a brief clash with the Persians and another in Egypt against the usurper Firmus, Aurelian was obliged to return to Palmyra in 273 when that city rebelled once more. This time, Aurelian allowed his soldiers to sack the city, and Palmyra never recovered. More honors came his way; he was now known as Parthicus Maximus and Restitutor Orientis ("Restorer of the East").

Rome 274 Aurelian turned his attention to the west and the Gallic Empire

Rome 274 In 274, the victorious emperor turned his attention to the west and the Gallic Empire which had already been reduced in size by Claudius II. Aurelian won this campaign largely through diplomacy; the "Gallic Emperor" Tetricus was willing to abandon his throne and allow Gaul and Britain to return to the Empire, but could not openly submit to Aurelian. Instead, the two seem to have conspired so that when the armies met at Châlons-en-Champagne that autumn, Tetricus simply deserted to the Roman camp and Aurelian easily defeated the Gallic army facing him. Tetricus was rewarded for his part in the conspiracy with a high-ranking position in Italy itself.

Rome Friday Dec 25, 274 Temple of the Sun

Rome Friday Dec 25, 274 Aurelian strengthened the position of the Sun god Sol Invictus as the main divinity of the Roman pantheon. His intention was to give to all the peoples of the Empire, civilians or soldiers, easterners or westerners, a single god they could believe in without betraying their own gods. The centre of the cult was a new temple, built in 274 and dedicated on December 25 of that year in the Campus Agrippae in Rome, with great decorations financed by the spoils of the Palmyrene Empire.

Roman Empire 275 Aurelian set out for another campaign against the Sassanids

Roman Empire 275 The deaths of the Sassanid Kings Shapur I (272) and Hormizd I (273) in quick succession, and the rise to power of a weakened ruler (Bahram I), presented an opportunity to attack the Sassanid Empire, and in 275 Aurelian set out for another campaign against the Sassanids. On his way, he suppressed a revolt in Gaul—possibly against Faustinus, an officer or usurper of Tetricus—and defeated barbarian marauders in Vindelicia (Germany).

Caenophrurium, Thrace Sep, 275 Aurelian died

Caenophrurium, Thrace Sep, 275 However, Aurelian never reached Persia, as he was murdered while waiting in Thrace to cross into Asia Minor. As an administrator, he had been strict and had handed out severe punishments to corrupt officials or soldiers. A secretary of his (called Eros by Zosimus) had told a lie on a minor issue. In fear of what the emperor might do, he forged a document listing the names of high officials marked by the emperor for execution and showed it to collaborators. The notarius Mucapor and other high-ranking officers of the Praetorian Guard, fearing punishment from the emperor, murdered him in September 275, in Caenophrurium, Thrace. Aurelian's enemies in the Senate briefly succeeded in passing damnatio memoriae on the emperor, but this was reversed before the end of the year, and Aurelian, like his predecessor Claudius II, was deified as Divus Aurelianus.

Roman Empire Saturday Sep 25, 275 Roman Empire 270s Antoniana Colonia Tyana, Cappadocia (Pressent-Day in Turkey) Jun, 276 Roman Empire Jul, 276 Tarsus, Cilicia Sep, 276 Florian died

Tarsus, Cilicia Sep, 276 Florian led his troops to Cilicia and billeted his forces in Tarsus. However many of his troops, who were unaccustomed to the hot climate of the area, fell ill due to a summer heatwave. Upon learning of this, Probus launched raids around the city, in order to weaken the morale of Florian's forces. This strategy was successful, and Florian lost control of his army, which in September rose up against him and killed him. In total, Florian's reign lasted less than three months.

Rome 276 Probus

Rome 276 Florian, the half-brother of Tacitus, also proclaimed himself emperor, and took control of Tacitus' army in Asia Minor, but was killed by his own soldiers after an indecisive campaign against Probus in the mountains of Cilicia. In contrast to Florian, who ignored the wishes of the senate, Probus referred his claim to Rome in a respectful dispatch. The senate enthusiastically ratified his pretensions.

Rome 280s Time of peace

Rome 280s The army discipline which Aurelian had repaired was cultivated and extended under Probus, who was however more shy in the practice of cruelty. One of his principles was never to allow the soldiers to be idle, and to employ them in time of peace on useful works, such as the planting of vineyards in Gaul, Pannonia, and other districts, in order to restart the economy in these devastated lands.

Roman Empire Sep, 282 Marcus Aurelius Carus

Roman Empire Sep, 282 Carus was apparently a senator and filled various posts, both civil and military, before being appointed prefect of the Praetorian Guard by the emperor Probus in 282. Two traditions surround his accession to the throne in August or September of 282. According to some mostly Latin sources, he was proclaimed emperor by the soldiers after the murder of Probus by a mutiny at Sirmium. Greek sources however claim that he rose against Probus in Raetia in usurpation and had him killed. Bestowing the title of Caesar upon his sons Carinus and Numerian, he left Carinus in charge of the western portion of the empire to look after some disturbances in Gaul and took Numerian with him on an expedition against the Persians, which had been contemplated by Probus.

Sirmium (Present-Day Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia) Sep, 282 Probus died

Sirmium (Present-Day Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia) Sep, 282 Probus was eager to start his eastern campaign, delayed by the revolts in the west. He left Rome in 282, traveling first towards Sirmium, his birth city. Different accounts of Probus's death exist. According to Joannes Zonaras, the commander of the Praetorian Guard Marcus Aurelius Carus had been proclaimed, more or less unwillingly, emperor by his troops. Probus sent some troops against the new usurper, but when those troops changed sides and supported Carus, Probus' remaining soldiers assassinated him at Sirmium (September/October 282). According to other sources, however, Probus was killed by disgruntled soldiers, who rebelled against his orders to be employed for civic purposes, like draining marshes. Allegedly, the soldiers were provoked when they overheard him lamenting the necessity of a standing army. Carus was proclaimed emperor after Probus' death and avenged the murder of his predecessor.

Roman Empire 283 Marcus Aurelius Carinus

Roman Empire 283 After the death of Emperor Probus in a spontaneous mutiny of the army in 282, his praetorian prefect, Carus, ascended to the throne. The latter, upon his departure for the Persian war, elevated his two sons to the title of Caesar. Carinus, the elder, was left to handle the affairs of the west in his absence, while the younger, Numerian, accompanied his father to the east.

Present-Day in Iraq 283 Carus captured Ctesiphon

Present-Day in Iraq 283 The Sassanid King Bahram II, limited by internal opposition and his troops occupied with a campaign in modern-day Afghanistan, could not effectively defend his territory. The Sasanians, faced with severe internal problems, could not mount an effective coordinated defense at the time; Carus and his army may have captured the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon. The victories of Carus avenged all the previous defeats suffered by the Romans against the Sassanids, and he received the title of Persicus Maximus.

Sasanian Empire (Present-Day in Iraq) 283 River Margus, Moesia Jul, 285 Battle of the Margus River

River Margus, Moesia Jul, 285 Carinus left Rome at once and set out for the east to meet Diocletian. On his way through Pannonia, he put down the usurper Sabinus Julianus and in July 285 he encountered the army of Diocletian at the Battle of the Margus River (the modern Morava River) in Moesia.

River Margus, Moesia Jul, 285 Carinus died

River Margus, Moesia Jul, 285 Historians differ on what then ensued. At the Battle of the Margus, according to one account, the valor of his troops had gained the day, but Carinus was assassinated by a tribune whose wife he had seduced. Another account represents the battle as resulting in a complete victory for Diocletian and claims that Carinus' army deserted him. This account may be confirmed by the fact that Diocletian kept in service Carinus' Praetorian Guard commander, Titus Claudius Aurelius Aristobulus.

Roman Empire 285 Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Thursday Jul 30, 285 Diocletian raised his fellow-officer Maximian to a co-emperor

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Thursday Jul 30, 285 Conflict boiled in every province, from Gaul to Syria, Egypt to the lower Danube. It was too much for one person to control, and Diocletian needed a lieutenant. At some time in 285 at Mediolanum (Milan), Diocletian raised his fellow-officer Maximian to the office of caesar, making him co-emperor.

Balkans Monday Nov 2, 285 Roman Empire Thursday Apr 1, 286 Maximian took up the title of Augustus

Roman Empire Thursday Apr 1, 286 Spurred by the crisis, on 1 April 286, Maximian took up the title of Augustus. His appointment is unusual in that it was impossible for Diocletian to have been present to witness the event. It has even been suggested that Maximian usurped the title and was only later recognized by Diocletian in hopes of avoiding civil war.

Milan, Italy Dec, 290 Diocletian met Maximian in Milan

Milan, Italy Dec, 290 Diocletian met Maximian in Milan in the winter of 290–91, either in late December 290 or January 291. The meeting was undertaken with a sense of solemn pageantry. The emperors spent most of their time in public appearances. It has been surmised that the ceremonies were arranged to demonstrate Diocletian's continuing support for his faltering colleague.

Milan, Italy Wednesday Mar 1, 293 Maximian gave Constantius the office of caesar

Milan, Italy Wednesday Mar 1, 293 Sometime after his return, and before 293, Diocletian transferred command of the war against Carausius from Maximian to Flavius Constantius, a former Governor of Dalmatia and a man of military experience stretching back to Aurelian's campaigns against Zenobia (272–73). He was Maximian's praetorian prefect in Gaul, and the husband to Maximian's daughter, Theodora. On 1 March 293 at Milan, Maximian gave Constantius the office of caesar.

Philippopolis (Present-Day Plovdiv, Bulgaria) 293 Roman Empire Tuesday Feb 24, 303 Diocletian's first "Edict against the Christians" was published

Roman Empire Tuesday Feb 24, 303 Diocletian's first "Edict against the Christians" was published. The edict ordered the destruction of Christian scriptures and places of worship across the empire and prohibited Christians from assembling for worship.

Nicomedia, Roman Empire Monday May 1, 305 Diocletian became the first Roman emperor to voluntarily abdicate his title

Nicomedia, Roman Empire Monday May 1, 305 On 1 May 305, Diocletian called an assembly of his generals, traditional companion troops, and representatives from distant legions. They met at the same hill, 5 kilometers (3.1 mi) out of Nicomedia, where Diocletian had been proclaimed emperor. In front of a statue of Jupiter, his patron deity, Diocletian addressed the crowd. With tears in his eyes, he told them of his weakness, his need for rest, and his will to resign. He declared that he needed to pass the duty of empire on to someone stronger. He thus became the first Roman emperor to voluntarily abdicate his title.

Roman Empire 305 Dalmatia, Roman Empire (Present-Day Split, Croatia) 305 Diocletian retired to his homeland

Dalmatia, Roman Empire (Present-Day Split, Croatia) 305 Diocletian retired to his homeland, Dalmatia. He moved into the expansive Diocletian's Palace, a heavily fortified compound located by the small town of Spalatum on the shores of the Adriatic Sea, and near the large provincial administrative center of Salona. The palace is preserved in great part to this day and forms the historic core of Split, the second-largest city of modern Croatia.

Roman Empire Wednesday Nov 11, 308 Galerius appoint Licinius to be Augustus in place of Severus

Roman Empire Wednesday Nov 11, 308 Galerius assumed the consular fasces in 308 with Diocletian as his colleague. In the autumn of 308, Galerius again conferred with Diocletian at Carnuntum (Petronell-Carnuntum, Austria). Diocletian and Maximian were both present on 11 November 308, to see Galerius appoint Licinius to be Augustus in place of Severus, who had died at the hands of Maxentius.

Roman Empire Wednesday Nov 11, 308 Serdica (Present-Day Sofia, Bulgeria) Friday May 5, 311 Roman Empire Friday May 5, 311 Dalmatia, Roman Empire (Present-Day Split, Croatia) Sunday Dec 3, 311 Mediolanum, Roman Empire (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Mar, 313 Mediolanum, Roman Empire (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 313 Edict of Milan

Mediolanum, Roman Empire (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 313 The Edict of Milan was the February AD 313 agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and Emperor Licinius, who controlled the Balkans, met in Mediolanum (modern-day Milan) and, among other things, agreed to change policies towards Christians following the edict of toleration issued by Emperor Galerius two years earlier in Serdica. The Edict of Milan gave Christianity legal status and a reprieve from persecution but did not make it the state church of the Roman Empire. That occurred in AD 380 with the Edict of Thessalonica.

Perinthus (Present-Day Marmara Ereğlisi, Turkey) Wednesday Apr 30, 313 Battle of Tzirallum

Perinthus (Present-Day Marmara Ereğlisi, Turkey) Wednesday Apr 30, 313 On 30 April 313, the two armies clashed at the Battle of Tzirallum, and in the ensuing battle, Daza's forces were crushed. Ridding himself of the imperial purple and dressing like a slave, Daza fled to Nicomedia.

Roman Empire 313 Tetrarchy was replaced by a system of two emperors

Roman Empire 313 Given that Constantine had already crushed his rival Maxentius in 312, the two men decided to divide the Roman world between them. As a result of this settlement, the Tetrarchy was replaced by a system of two emperors, called Augusti: Licinius became Augustus of the East, while his brother-in-law, Constantine, became Augustus of the West. After making the pact, Licinius rushed immediately to the East to deal with another threat, an invasion by the Persian Sassanid Empire.

Tarsus, Roman Empire Jul, 313 Maximinus Daza died

Tarsus, Roman Empire Jul, 313 Maximinus' death was variously ascribed "to despair, to poison, and to the divine justice". Based on descriptions of his death given by Eusebius, and Lactantius, as well as the appearance of Graves' ophthalmopathy in a Tetrarchic statue bust from Anthribis in Egypt, sometimes attributed to Maximinus, endocrinologist Peter D. Papapetrou has advanced a theory that Maximinus may have died from severe thyrotoxicosis due to Graves' disease.

Colonia Aurelia Cibalae (Present-Day Vinkovci, Croatia) 316 Battle of Cibalae

Colonia Aurelia Cibalae (Present-Day Vinkovci, Croatia) 316 In 314, a civil war erupted between Licinius and Constantine, in which Constantine used the pretext that Licinius was harboring Senecio, whom Constantine accused of plotting to overthrow him. Constantine prevailed at the Battle of Cibalae in Pannonia.

Adrianople (Present-Day Edirne, Turkey) Thursday Jul 3, 324 Battle of Adrianople

Adrianople (Present-Day Edirne, Turkey) Thursday Jul 3, 324 Then in 324, Constantine, tempted by the "advanced age and unpopular vices" of his colleague, again declared war against him and having defeated his army of 165,000 men at the Battle of Adrianople (3 July 324), succeeded in shutting him up within the walls of Byzantium.

Chrysopolis, near Chalcedon, Roman Empire (Present-Day Chalcedon, Turkey) Thursday Sep 18, 324 Battle of Chrysopolis

Chrysopolis, near Chalcedon, Roman Empire (Present-Day Chalcedon, Turkey) Thursday Sep 18, 324 The defeat of the superior fleet of Licinius in the Battle of the Hellespont by Crispus, Constantine's eldest son and Caesar, compelled his withdrawal to Bithynia, where the last stand was made; the Battle of Chrysopolis, near Chalcedon (18 September), resulted in Licinius' final submission.

Thessaloniki, Roman Empire (Present-Day Thessaloniki, Greece) 325 Licinius died

Thessaloniki, Roman Empire (Present-Day Thessaloniki, Greece) 325 In this conflict, Licinius was supported by the Gothic prince Alica. Due to the intervention of Flavia Julia Constantia, Constantine's sister and also Licinius' wife, both Licinius and his co-emperor Martinian were initially spared, Licinius being imprisoned in Thessalonica, Martinian in Cappadocia; however, both former emperors were subsequently executed. After his defeat, Licinius attempted to regain power with Gothic support, but his plans were exposed, and he was sentenced to death. While attempting to flee to the Goths, Licinius was apprehended at Thessalonica. Constantine had him hanged, accusing him of conspiring to raise troops among the barbarians.

Constantinople, Byzantine Empire (Present-Day Istanbul, Turkey) Sunday May 11, 330 Constantinople

Constantinople, Byzantine Empire (Present-Day Istanbul, Turkey) Sunday May 11, 330 Constantine decided to work on the Greek city of Byzantium, which offered the advantage of having already been extensively rebuilt on Roman patterns of urbanism, during the preceding century, by Septimius Severus and Caracalla, who had already acknowledged its strategic importance. The city was thus founded in 324, dedicated on 11 May 330, and renamed Constantinopolis ("Constantine's City" or Constantinople in English). Constantinople would be the capital of the Byzantine Empire.

Rome 43 BC Second Triumvirate

Rome 43 BC Octavian, the grandnephew and adopted son of Julius Caesar, had made himself a central military figure during the chaotic period following Caesar's assassination. In 43 BC at the age of twenty, he became one of the three members of the Second Triumvirate, a political alliance with Marcus Lepidus and Mark Antony.

Philippi, Macedonia (Present-Day in Greece) Friday Oct 3, 42 BC Rome 32 BC Ionian Sea Tuesday Sep 2, 31 BC Rome Saturday Jan 16, 27 BC Augustus

Rome Saturday Jan 16, 27 BC On 16 January 27 BC the Senate gave Octavian the new titles of Augustus and Princeps. Augustus is from the Latin word Augere (meaning to increase) and can be translated as "the illustrious one". It was a title of religious authority rather than political authority. His new title of Augustus was also more favorable than Romulus, the previous one which he styled for himself in reference to the story of the legendary founder of Rome, which symbolized a second founding of Rome.

Rome 27 BC Rome 23 BC Augustus renounced his consulship

Rome 23 BC Augustus renounced his consulship in 23 BC, but retained his consular imperium, leading to a second compromise between Augustus and the Senate known as the Second Settlement. Augustus was granted the authority of a tribune (tribunicia potestas), though not the title, which allowed him to call together the Senate and people at will and lay business before it, veto the actions of either the Assembly or the Senate, preside over elections, and it gave him the right to speak first at any meeting.

Spain 19 BC Rome 6 BC