What happened in history in Italy

Check most memorable events in history in Italy.

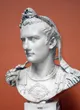

Rome 13 Nola (Present-Day in Naples, Italy) Tuesday Aug 19, 14 Rome Wednesday Sep 17, 14 Roman EmpireTiberius's reign

Rome Wednesday Sep 17, 14 The early years of Tiberius's reign were relatively peaceful. Tiberius secured the overall power of Rome and enriched its treasury. However, his rule soon became characterized by paranoia. He began a series of treason trials and executions, which continued until his death in 37.

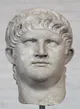

Roman Empire 31 Miseno, Italy, Roman Empire Monday Mar 16, 37 Roman Empire Monday Mar 16, 37 Roman Empire 37 Roman EmpireCaligula's Illness

Roman Empire 37 The Caligula that emerged in late 37 demonstrated features of mental instability that led modern commentators to diagnose him with such illnesses as encephalitis, which can cause mental derangement, hyperthyroidism, or even a nervous breakdown (perhaps brought on by the stress of his position).

Palatine Hill, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Thursday Jan 24, 41 Roman EmpireCaligula was assassinated

Palatine Hill, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Thursday Jan 24, 41 In 41, Caligula was assassinated by the commander of the guard Cassius Chaerea. Also killed were his fourth wife Caesonia and their daughter Julia Drusilla. For two days following his assassination, the senate debated the merits of restoring the Republic.

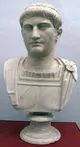

Rome Thursday Jan 24, 41 Roman EmpireClaudius

Rome Thursday Jan 24, 41 Claudius was a younger brother of Germanicus and had long been considered a weakling and a fool by the rest of his family. The Praetorian Guard, however, acclaimed him as emperor. Claudius was neither paranoid like his uncle Tiberius, nor insane like his nephew Caligula, and was, therefore, able to administer the Empire with reasonable ability.

Gardens of Lucullus, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire 48 Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Tuesday Oct 13, 54 Rome Tuesday Oct 13, 54 Rome Friday Jul 18, 64 Roman EmpireGreat Fire of Rome

Rome Friday Jul 18, 64 He believed himself a god and decided to build an opulent palace for himself. The so-called Domus Aurea, meaning golden house in Latin, was constructed atop the burnt remains of Rome after the Great Fire of Rome (64). Nero was ultimately responsible for the fire. By this time Nero was hugely unpopular despite his attempts to blame the Christians for most of his regime's problems.

Rome Friday Jun 8, 68 Roman EmpireServius Sulpicius Galba

Rome Friday Jun 8, 68 Servius Sulpicius Galba, born as Lucius Livius Ocella Sulpicius Galba, was a Roman emperor who ruled from AD 68 to 69. He was the first emperor in the Year of the Four Emperors and assumed the position following Emperor Nero's suicide. Galba's physical weakness and general apathy led to him being selected over by favorites. Unable to gain popularity with the people or maintain the support of the Praetorian Guard, Galba was murdered by Otho, who became emperor in his place.

Outside Rome Saturday Jun 9, 68 Rome Tuesday Jan 15, 69 Roman EmpireMarcus Otho

Rome Tuesday Jan 15, 69 Marcus Otho was Roman emperor for three months, from 15 January to 16 April 69. He was the second emperor of the Year of the Four Emperors. Inheriting the problem of the rebellion of Vitellius, commander of the army in Germania Inferior, Otho led a sizeable force that met Vitellius' army at the Battle of Bedriacum. After initial fighting resulted in 40,000 casualties, and a retreat of his forces, Otho committed suicide rather than fight on, and Vitellius was proclaimed emperor.

Rome Friday Apr 19, 69 Roman EmpireAulus Vitellius

Rome Friday Apr 19, 69 Aulus Vitellius was Roman Emperor for eight months, from 19 April to 20 December AD 69. Vitellius was proclaimed emperor following the quick succession of the previous emperors Galba and Otho, in a year of civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors. His claim to the throne was soon challenged by legions stationed in the eastern provinces, who proclaimed their commander Vespasian emperor instead. War ensued, leading to a crushing defeat for Vitellius at the Second Battle of Bedriacum in northern Italy. Once he realized his support was wavering, Vitellius prepared to abdicate in favor of Vespasian. He was not allowed to do so by his supporters, resulting in a brutal battle for Rome between Vitellius' forces and the armies of Vespasian. He was executed in Rome by Vespasian's soldiers on 20 December 69.

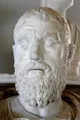

Rome Monday Jul 1, 69 Rome 69 Rome Saturday Jun 24, 79 Pompeii, Italy, Roman Empire 79 Rome Sunday Sep 14, 81 Rome Tuesday Sep 18, 96 Roman EmpireNerva

Rome Tuesday Sep 18, 96 On 18 September 96, Domitian was assassinated in a palace conspiracy involving members of the Praetorian Guard and several of his freedmen. On the same day, Nerva was declared emperor by the Roman Senate. As the new ruler of the Roman Empire, he vowed to restore liberties that had been curtailed during the autocratic government of Domitian.

Rome 97 Roman EmpireNerva adopted Trajan

Rome 97 Nerva's brief reign was marred by financial difficulties and his inability to assert his authority over the Roman army. A revolt by the Praetorian Guard in October 97 essentially forced him to adopt an heir. After some deliberation, Nerva adopted Trajan, a young and popular general, as his successor.

Gardens of Sallust, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Monday Jan 27, 98 Rome 105 Rome, Roman Empire 113 LibrariesUlpian Library

Rome, Roman Empire 113 One of the best preserved was the ancient Ulpian Library built by the Emperor Trajan. Completed in 112/113 AD, the Ulpian Library was part of Trajan's Forum built on the Capitoline Hill. Trajan's Column separated the Greek and Latin rooms which faced each other. The structure was approximately fifty feet high with the peak of the roof reaching almost seventy feet.

Roman Empire 117 Roman Empire Wednesday Aug 11, 117 Roman Empire 117 Roman EmpireFour executions

Roman Empire 117 Hadrian relieved Judea's governor, the outstanding Moorish general Lusius Quietus, of his personal guard of Moorish auxiliaries; then he moved on to quell disturbances along the Danube frontier. There was no public trial for the four – they were tried in absentia, hunted down, and killed. Hadrian claimed that Attianus had acted on his own initiative, and rewarded him with senatorial status and consular rank; then pensioned him off, no later than 120. Hadrian assured the senate that henceforth their ancient right to prosecute and judge their own would be respected. In Rome, Hadrian's former guardian and current Praetorian Prefect, Attianus, claimed to have uncovered a conspiracy involving Lusius Quietus and three other leading senators, Lucius Publilius Celsus, Aulus Cornelius Palma Frontonianus, and Gaius Avidius Nigrinus.

Roman Empire 120 Roman Empire 125 Roman Empire Tuesday Feb 25, 138 Roman EmpireAntoninus Pius "adopted son"

Roman Empire Tuesday Feb 25, 138 Antoninus Pius acquired much favor with Hadrian, who adopted him as his son and successor on 25 February 138, after the death of his first adopted son Lucius Aelius, on the condition that Antoninus would, in turn, adopt Marcus Annius Verus, the son of his wife's brother, and Lucius, son of Lucius Aelius, who afterward became the emperors, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Roman Empire Friday Jul 11, 138 Roman Empire 140 United Kingdom 142 Roman EmpireConstruction began of Antonine Wall

United Kingdom 142 It was however in Britain that Antoninus decided to follow a new, more aggressive path, with the appointment of a new governor in 139, Quintus Lollius Urbicus, a native of Numidia and previously governor of Germania Inferior as well as a new man. Under instructions from the emperor, Lollius undertook an invasion of southern Scotland, winning some significant victories, and constructing the Antonine Wall from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde. The wall, however, was soon gradually decommissioned during the mid-150s and eventually abandoned late during the reign (early 160s), for reasons that are still not quite clear.

Lorium, Etruria, Italy, Roman Empire Saturday Mar 7, 161 Rome Saturday Mar 7, 161 Roman EmpireMarcus Aurelius

Rome Saturday Mar 7, 161 Marcus was effectively the sole ruler of the Empire. The formalities of the position would follow. The senate would soon grant him the name Augustus and the title imperator, and he would soon be formally elected as Pontifex Maximus, chief priest of the official cults. Marcus made some show of resistance: the biographer writes that he was 'compelled' to take imperial power.

Roman Empire 161 Roman Empire 2nd Century Disasters with highest death tollsAntonine Plague

Roman Empire 2nd Century The Antonine Plague of 165 to 180 AD, also known as the Plague of Galen (from the name of the Greek physician living in the Roman Empire who described it), was an ancient pandemic brought back to the Roman Empire by troops returning from campaigns in the Near East. The disease broke out again nine years later, according to the Roman historian Dio Cassius (155–235), causing up to 2,000 deaths a day in Rome, one quarter of those who were affected, giving the disease a mortality rate of about 25%. The total deaths have been estimated at five million, and the disease killed as much as one-third of the population in some areas and devastated the Roman army.

Altinum, Italy, Roman Empire 169 Roman EmpireLucius Verus died

Altinum, Italy, Roman Empire 169 In the spring of 168 war broke out on the Danubian border when the Marcomanni invaded the Roman territory. This war would last until 180, but Verus did not see the end of it. In 168, as Verus and Marcus Aurelius returned to Rome from the field, Verus fell ill with symptoms attributed to food poisoning, dying after a few days (169).

Roman Empire 179 Rome, Roman Empire 182 Roman EmpireAssassination attempt (Commodus)

Rome, Roman Empire 182 The first crisis of the reign came in 182 when Lucilla engineered a conspiracy against her brother. Her motive is alleged to have been the envy of Empress Crispina. Her husband, Pompeianus, was not involved, but two men alleged to have been her lovers, Marcus Ummidius Quadratus Annianus (the consul of 167, who was also her first cousin) and Appius Claudius Quintianus, attempted to murder Commodus as he entered a theater. They bungled the job and were seized by the emperor's bodyguard.

Rome, Roman Empire Monday Dec 31, 192 Rome, Roman Empire Thursday Mar 28, 193 Roman EmpirePertinax died

Rome, Roman Empire Thursday Mar 28, 193 On 28 March 193, Pertinax was at his palace when a contingent of some three hundred soldiers of the Praetorian Guard rushed the gates (two hundred according to Cassius Dio). Sources suggest that they had received only half their promised pay. Neither the guards on duty nor the palace officials chose to resist them. Pertinax sent Laetus to meet them, but he chose to side with the insurgents instead and deserted the emperor.

Rome 193 Roman EmpireThrone was to be sold

Rome 193 After the murder of Pertinax on 28 March 193, the Praetorian guard announced that the throne was to be sold to the man who would pay the highest price. Titus Flavius Claudius Sulpicianus, prefect of Rome and Pertinax's father-in-law, who was in the Praetorian camp ostensibly to calm the troops, began making offers for the throne. Meanwhile, Julianus also arrived at the camp, and since his entrance was barred, shouted out offers to the guard. After hours of bidding, Sulpicianus promised 20,000 sesterces to every soldier; Julianus, fearing that Sulpicianus would gain the throne, then offered 25,000. The guards closed with the offer of Julianus, threw open the gates, and proclaimed him emperor. Threatened by the military, the senate also declared him emperor. His wife and his daughter both received the title Augusta.

Rome Thursday Mar 28, 193 Roman EmpireDidius Julianus

Rome Thursday Mar 28, 193 Because Julianus bought his position rather than acquiring it conventionally through succession or conquest, he was a deeply unpopular emperor. When Julianus appeared in public, he frequently was greeted with groans and shouts of "robber and parricide." Once, a mob even obstructed his progress to the Capitol by pelting him with large stones.

Rome Sunday Jun 2, 193 Rome Tuesday Dec 17, 211 Roman EmpireCaracalla tried unsuccessfully to murder Geta

Rome Tuesday Dec 17, 211 The current stability of their joint government was only through the mediation and leadership of their mother, Julia Domna, accompanied by other senior courtiers and generals in the military. The historian Herodian asserted that the brothers decided to split the empire into two halves, but with the strong opposition of their mother, the idea was rejected, when, by the end of 211, the situation had become unbearable. Caracalla tried unsuccessfully to murder Geta during the festival of Saturnalia (17 December).

Rome Thursday Dec 26, 211 Rome Friday Apr 11, 217 Roman EmpireMacrinus was declared augustus

Rome Friday Apr 11, 217 On April 8, 217, Caracalla was assassinated traveling to Carrhae. Three days later, Macrinus was declared Augustus. Diadumenian was the son of Macrinus, born in 208. He was given the title Caesar in 217, when his father became augustus, and raised to co-Augustus the following year.

Rome Wednesday Mar 6, 222 Roman EmpireA romur

Rome Wednesday Mar 6, 222 Alexander Severus was adopted as son and caesar by his slightly older and very unpopular cousin, the emperor Elagabalus at the urging of the influential and powerful Julia Maesa — who was the grandmother of both cousins and who had arranged for the emperor's acclamation by the Third Legion. On March 6, 222, when Alexander was just fourteen, a rumor went around the city troops that Alexander had been killed, triggering a revolt of the guards that had sworn his safety from Elegabalus and his accession as emperor.

Rome Wednesday Mar 13, 222 Roman EmpireSeverus Alexander

Rome Wednesday Mar 13, 222 The running of the Empire during this time was mainly left to his grandmother and mother (Julia Soaemias). Seeing that her grandson's outrageous behavior could mean the loss of power, Julia Maesa persuaded Elagabalus to accept his cousin Alexander Severus as caesar (and thus the nominal emperor-to-be). However, Alexander was popular with the troops, who viewed their new emperor with dislike: when Elagabalus, jealous of this popularity, removed the title of caesar from his nephew, the enraged Praetorian Guard swore to protect him. Elagabalus and his mother were murdered in a Praetorian Guard camp mutiny.

Terni, Italy 226 Rome, Italy 3rd Century Valentine's DayThe legend of Saint Valentine

Rome, Italy 3rd Century Another legend is that Valentine refused to sacrifice to pagan gods. Being imprisoned for this, Valentine gave his testimony in prison and through his prayers healed the jailer's daughter who was suffering from blindness. On the day of his execution, he left her a note that was signed, "Your Valentine". there are two possible figures behind the character of Saint Valentine Saint Valantine of Rome and Saint Valentine of Terni.

Rome Sunday Mar 22, 235 Roman Empire 3rd Century Byzantine EmpireCrisis of the Third Century

Roman Empire 3rd Century The Roman army succeeded in conquering many territories covering the Mediterranean region and coastal regions in southwestern Europe and North Africa. These territories were home to many different cultural groups, both urban populations, and rural populations. The West also suffered more heavily from the instability of the 3rd century. This distinction between the established Hellenised East and the younger Latinised West persisted and became increasingly important in later centuries, leading to a gradual estrangement of the two worlds.

Rome Mar, 238 Roman EmpireGordian I proclaim himself emperor

Rome Mar, 238 Some young aristocrats in Africa murdered the imperial tax-collector then approached the regional governor, Gordian, and insisted that he proclaim himself emperor. Gordian agreed reluctantly, but as he was almost 80 years old, he decided to make his son joint emperor, with equal power. The Senate recognized father and son as emperors Gordian I and Gordian II, respectively. Their reign, however, lasted for only 20 days. Capelianus, the governor of the neighboring province of Numidia, held a grudge against the Gordians. He led an army to fight them and defeated them decisively at Carthage. Gordian II was killed in the battle, and on hearing this news, Gordian I hanged himself. Gordian I and II were deified by the senate.

Rome Sunday Apr 22, 238 Roman EmpirePupienus and Balbinus joint emperors

Rome Sunday Apr 22, 238 Meanwhile, Maximinus, now declared a public enemy, had already begun to march on Rome with another army. The senate's previous candidates, the Gordians, had failed to defeat him, and knowing that they stood to die if he succeeded, the senate needed a new emperor to defeat him. With no other candidates in view, on 22 April 238, they elected two elderly senators, Pupienus and Balbinus (who had both been part of a special senatorial commission to deal with Maximinus), as joint emperors. Therefore, Marcus Antonius Gordianus Pius, the thirteen-year-old grandson of Gordian I, was nominated as emperor Gordian III, holding power only nominally in order to appease the population of the capital, which was still loyal to the Gordian family.

Aquileia, Italy, Roman Empire Thursday May 10, 238 Rome Sunday Jul 29, 238 Roman EmpireGordian III was proclaimed sole emperor

Rome Sunday Jul 29, 238 The situation for Pupienus and Balbinus, despite Maximinus' death, was doomed from the start with popular riots, military discontent and enormous fire that consumed Rome in June 238. On July 29, Pupienus and Balbinus were killed by the Praetorian Guard and Gordian was proclaimed sole emperor.

Rome Feb, 244 Verona, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 249 Roman EmpirePhilip was killed

Verona, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 249 Although Decius tried to come to terms with Philip, Philip's army met the usurper near modern Verona that summer. Decius easily won the battle and Philip was killed sometime in September 249, either in the fighting or assassinated by his own soldiers who were eager to please the new ruler. Philip's eleven-year-old son and heir may have been killed with his father and Priscus disappeared without a trace.

Italy 250 Rome Jun, 251 Roman EmpireTrebonianus Gallus

Rome Jun, 251 In June 251, Decius and his co-emperor and son Herennius Etruscus died in the Battle of Abrittus at the hands of the Goths they were supposed to punish for raids into the empire. According to rumors supported by Dexippus (a contemporary Greek historian) and the thirteenth Sibylline Oracle, Decius' failure was largely owing to Gallus, who had conspired with the invaders. In any case, when the army heard the news, the soldiers proclaimed Gallus emperor, despite Hostilian, Decius' surviving son, ascending the imperial throne in Rome. This action of the army, and the fact that Gallus seems to have been on good terms with Decius' family, makes Dexippus' allegation improbable. Gallus did not back down from his intention to become emperor, but accepted Hostilian as co-emperor, perhaps to avoid the damage of another civil war.

Interamna (Present-Day Terni, Italy) Aug, 253 Roman EmpireGallus was killed

Interamna (Present-Day Terni, Italy) Aug, 253 Since the army was no longer pleased with the Emperor, the soldiers proclaimed Aemilianus emperor. With a usurper, supported by Pauloctus, threatening the throne, Gallus prepared for a fight. He recalled several legions and ordered reinforcements to return to Rome from Gaul under the command of the future emperor Publius Licinius Valerianus. Despite these dispositions, Aemilianus marched onto Italy ready to fight for his claim and caught Gallus at Interamna (modern Terni) before the arrival of Valerianus. What exactly happened is not clear. Later sources claim that after an initial defeat, Gallus and Volusianus were murdered by their own troops; or Gallus did not have the chance to face Aemilianus at all because his army went over to the usurper. In any case, both Gallus and Volusianus were killed in August 253.

Rome 253 Roman EmpireMarcus Aemilius Aemilianus "Aemilian"

Rome 253 Aemilian continued towards Rome. The Roman senate, after a short opposition, decided to recognize him as emperor. According to some sources, Aemilian then wrote to the Senate, promising to fight for the Empire in Thrace and against Persia and to relinquish his power to the Senate, of which he considered himself a general.

Spoletium, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 253 Roman EmpireAemilian died

Spoletium, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 253 Valerian, governor of the Rhine provinces, was on his way south with an army which, according to Zosimus, had been called in as reinforcement by Gallus. But modern historians believe this army, possibly mobilized for an incumbent campaign in the East, moved only after Gallus' death to support Valerian's bid for power. Emperor Aemilian's men, fearful of civil war and Valerian's larger force, mutinied. They killed Aemilian at Spoletium or at the Sanguinarium bridge, between Oriculum and Narnia (halfway between Spoletium and Rome), and recognized Valerian as the new emperor.

Rome Saturday Oct 22, 253 Roman EmpireValerian's first act as emperor

Rome Saturday Oct 22, 253 Valerian's first act as emperor on October 22, 253, was to appoint his son Gallienus caesar. Early in his reign, affairs in Europe went from bad to worse, and the whole West fell into disorder. In the East, Antioch had fallen into the hands of a Sassanid vassal and Armenia was occupied by Shapur I (Sapor).

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 268 Roman EmpireGallienus was challenged by Aureolus

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 268 In 268, at some time before or soon after the battle of Naissus, the authority of Gallienus was challenged by Aureolus, commander of the cavalry stationed in Mediolanum (Milan), who was supposed to keep an eye on Postumus. Instead, he acted as deputy to Postumus until the very last days of his revolt, when he seems to have claimed the throne for himself. The decisive battle took place at what is now Pontirolo Nuovo near Milan; Aureolus was clearly defeated and driven back to Milan. Gallienus laid siege to the city but was murdered during the siege. There are differing accounts of the murder, but the sources agree that most of Gallienus' officials wanted him dead.

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Sep, 268 Roman EmpireGallienus died

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Sep, 268 Cecropius, commander of the Dalmatians, spread the word that the forces of Aureolus were leaving the city, and Gallienus left his tent without his bodyguard, only to be struck down by Cecropius. According to Aurelius Victor and Zonaras, on hearing the news that Gallienus was dead, the Senate in Rome ordered the execution of his family (including his brother Valerianus and son Marinianus) and their supporters, just before receiving a message from Claudius to spare their lives and deify his predecessor.

Rome Sep, 268 Roman EmpireClaudius Gothicus was chosen by the army

Rome Sep, 268 Whichever story is true, Gallienus was killed in the summer of 268, and Claudius was chosen by the army outside of Milan to succeed him. Accounts tell of people hearing the news of the new emperor and reacting by murdering Gallienus' family members until Claudius declared he would respect the memory of his predecessor. Claudius had the deceased emperor deified and buried in a family tomb on the Appian Way. The traitor Aureolus was not treated with the same reverence, as he was killed by his besiegers after a failed attempt to surrender.

Rome, Italy Tuesday Feb 16, 269 Rome 270 Roman EmpireQuintillus

Rome 270 Quintillus was declared emperor either by the Senate or by his brother's soldiers upon the latter's death in 270. Eutropius reports Quintillus to have been elected by soldiers of the Roman army immediately following the death of his brother; the choice was reportedly approved by the Roman Senate.

Aquileia, Italy, Roman Empire 270 Roman EmpireQuintillus death

Aquileia, Italy, Roman Empire 270 The few records of Quintillus' reign are contradictory. They disagree on the length of his reign, variously reported to have lasted as few as 17 days and as many as 177 days (about six months). Records also disagree on the cause of his death.

Northern Italy 270 Roman EmpireAurelian campaigned in northern Italia

Northern Italy 270 The first actions of the new Emperor were aimed at strengthening his own position in his territories. Late in 270, Aurelian campaigned in northern Italia against the Vandals, Juthungi, and Sarmatians, expelling them from Roman territory. To celebrate these victories, Aurelian was granted the title of Germanicus Maximus.

Roman Empire 272 Roman EmpireAurelian turned his attention to the lost eastern provinces of the empire

Roman Empire 272 In 272, Aurelian turned his attention to the lost eastern provinces of the empire, the Palmyrene Empire, ruled by Queen Zenobia from the city of Palmyra. Zenobia had carved out her own empire, encompassing Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and large parts of Asia Minor. The Syrian queen cut off Rome's shipments of grain, and in a matter of weeks, the Romans started running low on bread. In the beginning, Aurelian had been recognized as Emperor, while Vaballathus, the son of Zenobia, held the title of rex and imperator ("king" and "supreme military commander"), but Aurelian decided to invade the eastern provinces as soon as he felt his army to be strong enough.

Rome 272 Roman EmpireAurelian is believed to have terminated Trajan's alimenta program

Rome 272 Aurelian is believed to have terminated Trajan's alimenta program. Roman prefect Titus Flavius Postumius Quietus was the last known official in charge of the alimenta, in 272 AD. If Aurelian "did suppress this food distribution system, he most likely intended to put into effect a more radical reform."

Rome 274 Roman EmpireAurelian turned his attention to the west and the Gallic Empire

Rome 274 In 274, the victorious emperor turned his attention to the west and the Gallic Empire which had already been reduced in size by Claudius II. Aurelian won this campaign largely through diplomacy; the "Gallic Emperor" Tetricus was willing to abandon his throne and allow Gaul and Britain to return to the Empire, but could not openly submit to Aurelian. Instead, the two seem to have conspired so that when the armies met at Châlons-en-Champagne that autumn, Tetricus simply deserted to the Roman camp and Aurelian easily defeated the Gallic army facing him. Tetricus was rewarded for his part in the conspiracy with a high-ranking position in Italy itself.

Rome Friday Dec 25, 274 Roman EmpireTemple of the Sun

Rome Friday Dec 25, 274 Aurelian strengthened the position of the Sun god Sol Invictus as the main divinity of the Roman pantheon. His intention was to give to all the peoples of the Empire, civilians or soldiers, easterners or westerners, a single god they could believe in without betraying their own gods. The centre of the cult was a new temple, built in 274 and dedicated on December 25 of that year in the Campus Agrippae in Rome, with great decorations financed by the spoils of the Palmyrene Empire.

Roman Empire 275 Roman EmpireAurelian set out for another campaign against the Sassanids

Roman Empire 275 The deaths of the Sassanid Kings Shapur I (272) and Hormizd I (273) in quick succession, and the rise to power of a weakened ruler (Bahram I), presented an opportunity to attack the Sassanid Empire, and in 275 Aurelian set out for another campaign against the Sassanids. On his way, he suppressed a revolt in Gaul—possibly against Faustinus, an officer or usurper of Tetricus—and defeated barbarian marauders in Vindelicia (Germany).

Roman Empire Saturday Sep 25, 275 Roman Empire 270s Roman Empire Jul, 276 Rome 276 Roman EmpireProbus

Rome 276 Florian, the half-brother of Tacitus, also proclaimed himself emperor, and took control of Tacitus' army in Asia Minor, but was killed by his own soldiers after an indecisive campaign against Probus in the mountains of Cilicia. In contrast to Florian, who ignored the wishes of the senate, Probus referred his claim to Rome in a respectful dispatch. The senate enthusiastically ratified his pretensions.

Rome 280s Roman EmpireTime of peace

Rome 280s The army discipline which Aurelian had repaired was cultivated and extended under Probus, who was however more shy in the practice of cruelty. One of his principles was never to allow the soldiers to be idle, and to employ them in time of peace on useful works, such as the planting of vineyards in Gaul, Pannonia, and other districts, in order to restart the economy in these devastated lands.

Roman Empire 283 Roman EmpireMarcus Aurelius Carinus

Roman Empire 283 After the death of Emperor Probus in a spontaneous mutiny of the army in 282, his praetorian prefect, Carus, ascended to the throne. The latter, upon his departure for the Persian war, elevated his two sons to the title of Caesar. Carinus, the elder, was left to handle the affairs of the west in his absence, while the younger, Numerian, accompanied his father to the east.

Roman Empire 285 Roman EmpireDiocletian

Roman Empire 285 Diocletian may have become involved in battles against the Quadi and Marcomanni immediately after the Battle of the Margus. He eventually made his way to northern Italy and made an imperial government, but it is not known whether he visited the city of Rome at this time.

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Thursday Jul 30, 285 Roman EmpireDiocletian raised his fellow-officer Maximian to a co-emperor

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Thursday Jul 30, 285 Conflict boiled in every province, from Gaul to Syria, Egypt to the lower Danube. It was too much for one person to control, and Diocletian needed a lieutenant. At some time in 285 at Mediolanum (Milan), Diocletian raised his fellow-officer Maximian to the office of caesar, making him co-emperor.

Roman Empire Thursday Apr 1, 286 Roman EmpireMaximian took up the title of Augustus

Roman Empire Thursday Apr 1, 286 Spurred by the crisis, on 1 April 286, Maximian took up the title of Augustus. His appointment is unusual in that it was impossible for Diocletian to have been present to witness the event. It has even been suggested that Maximian usurped the title and was only later recognized by Diocletian in hopes of avoiding civil war.

Milan, Italy Dec, 290 Roman EmpireDiocletian met Maximian in Milan

Milan, Italy Dec, 290 Diocletian met Maximian in Milan in the winter of 290–91, either in late December 290 or January 291. The meeting was undertaken with a sense of solemn pageantry. The emperors spent most of their time in public appearances. It has been surmised that the ceremonies were arranged to demonstrate Diocletian's continuing support for his faltering colleague.

Milan, Italy Wednesday Mar 1, 293 Roman EmpireMaximian gave Constantius the office of caesar

Milan, Italy Wednesday Mar 1, 293 Sometime after his return, and before 293, Diocletian transferred command of the war against Carausius from Maximian to Flavius Constantius, a former Governor of Dalmatia and a man of military experience stretching back to Aurelian's campaigns against Zenobia (272–73). He was Maximian's praetorian prefect in Gaul, and the husband to Maximian's daughter, Theodora. On 1 March 293 at Milan, Maximian gave Constantius the office of caesar.

Roman Empire 293 Byzantine EmpireThe Tetrarchy systems

Roman Empire 293 An early instance of the partition of the Empire into East and West occurred in 293 when Emperor Diocletian created a new administrative system (the tetrarchy), to guarantee security in all endangered regions of his Empire. He associated himself with a co-emperor (Augustus), and each co-emperor then adopted a young colleague given the title of Caesar, to share in their rule and eventually to succeed the senior partner. Each tetrarch was in charge of a part of the Empire.

Roman Empire 305 Roman Empire Wednesday Nov 11, 308 Roman EmpireGalerius appoint Licinius to be Augustus in place of Severus

Roman Empire Wednesday Nov 11, 308 Galerius assumed the consular fasces in 308 with Diocletian as his colleague. In the autumn of 308, Galerius again conferred with Diocletian at Carnuntum (Petronell-Carnuntum, Austria). Diocletian and Maximian were both present on 11 November 308, to see Galerius appoint Licinius to be Augustus in place of Severus, who had died at the hands of Maxentius.

Mediolanum, Roman Empire (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Mar, 313 Mediolanum, Roman Empire (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 313 Roman EmpireEdict of Milan

Mediolanum, Roman Empire (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 313 The Edict of Milan was the February AD 313 agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and Emperor Licinius, who controlled the Balkans, met in Mediolanum (modern-day Milan) and, among other things, agreed to change policies towards Christians following the edict of toleration issued by Emperor Galerius two years earlier in Serdica. The Edict of Milan gave Christianity legal status and a reprieve from persecution but did not make it the state church of the Roman Empire. That occurred in AD 380 with the Edict of Thessalonica.

Rome, Roman Empire 313 Roman Empire 313 Roman EmpireTetrarchy was replaced by a system of two emperors

Roman Empire 313 Given that Constantine had already crushed his rival Maxentius in 312, the two men decided to divide the Roman world between them. As a result of this settlement, the Tetrarchy was replaced by a system of two emperors, called Augusti: Licinius became Augustus of the East, while his brother-in-law, Constantine, became Augustus of the West. After making the pact, Licinius rushed immediately to the East to deal with another threat, an invasion by the Persian Sassanid Empire.

Eastern Roman EmpireI "Italy" 395 Rome 13 Nola (Present-Day in Naples, Italy) Tuesday Aug 19, 14 Rome Wednesday Sep 17, 14 Roman EmpireTiberius's reign

Rome Wednesday Sep 17, 14 The early years of Tiberius's reign were relatively peaceful. Tiberius secured the overall power of Rome and enriched its treasury. However, his rule soon became characterized by paranoia. He began a series of treason trials and executions, which continued until his death in 37.

Roman Empire 31 Miseno, Italy, Roman Empire Monday Mar 16, 37 Roman Empire Monday Mar 16, 37 Roman Empire 37 Roman EmpireCaligula's Illness

Roman Empire 37 The Caligula that emerged in late 37 demonstrated features of mental instability that led modern commentators to diagnose him with such illnesses as encephalitis, which can cause mental derangement, hyperthyroidism, or even a nervous breakdown (perhaps brought on by the stress of his position).

Palatine Hill, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Thursday Jan 24, 41 Roman EmpireCaligula was assassinated

Palatine Hill, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Thursday Jan 24, 41 In 41, Caligula was assassinated by the commander of the guard Cassius Chaerea. Also killed were his fourth wife Caesonia and their daughter Julia Drusilla. For two days following his assassination, the senate debated the merits of restoring the Republic.

Rome Thursday Jan 24, 41 Roman EmpireClaudius

Rome Thursday Jan 24, 41 Claudius was a younger brother of Germanicus and had long been considered a weakling and a fool by the rest of his family. The Praetorian Guard, however, acclaimed him as emperor. Claudius was neither paranoid like his uncle Tiberius, nor insane like his nephew Caligula, and was, therefore, able to administer the Empire with reasonable ability.

Gardens of Lucullus, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire 48 Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Tuesday Oct 13, 54 Rome Tuesday Oct 13, 54 Rome Friday Jul 18, 64 Roman EmpireGreat Fire of Rome

Rome Friday Jul 18, 64 He believed himself a god and decided to build an opulent palace for himself. The so-called Domus Aurea, meaning golden house in Latin, was constructed atop the burnt remains of Rome after the Great Fire of Rome (64). Nero was ultimately responsible for the fire. By this time Nero was hugely unpopular despite his attempts to blame the Christians for most of his regime's problems.

Rome Friday Jun 8, 68 Roman EmpireServius Sulpicius Galba

Rome Friday Jun 8, 68 Servius Sulpicius Galba, born as Lucius Livius Ocella Sulpicius Galba, was a Roman emperor who ruled from AD 68 to 69. He was the first emperor in the Year of the Four Emperors and assumed the position following Emperor Nero's suicide. Galba's physical weakness and general apathy led to him being selected over by favorites. Unable to gain popularity with the people or maintain the support of the Praetorian Guard, Galba was murdered by Otho, who became emperor in his place.

Outside Rome Saturday Jun 9, 68 Rome Tuesday Jan 15, 69 Roman EmpireMarcus Otho

Rome Tuesday Jan 15, 69 Marcus Otho was Roman emperor for three months, from 15 January to 16 April 69. He was the second emperor of the Year of the Four Emperors. Inheriting the problem of the rebellion of Vitellius, commander of the army in Germania Inferior, Otho led a sizeable force that met Vitellius' army at the Battle of Bedriacum. After initial fighting resulted in 40,000 casualties, and a retreat of his forces, Otho committed suicide rather than fight on, and Vitellius was proclaimed emperor.

Rome Friday Apr 19, 69 Roman EmpireAulus Vitellius

Rome Friday Apr 19, 69 Aulus Vitellius was Roman Emperor for eight months, from 19 April to 20 December AD 69. Vitellius was proclaimed emperor following the quick succession of the previous emperors Galba and Otho, in a year of civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors. His claim to the throne was soon challenged by legions stationed in the eastern provinces, who proclaimed their commander Vespasian emperor instead. War ensued, leading to a crushing defeat for Vitellius at the Second Battle of Bedriacum in northern Italy. Once he realized his support was wavering, Vitellius prepared to abdicate in favor of Vespasian. He was not allowed to do so by his supporters, resulting in a brutal battle for Rome between Vitellius' forces and the armies of Vespasian. He was executed in Rome by Vespasian's soldiers on 20 December 69.

Rome Monday Jul 1, 69 Rome 69 Rome Saturday Jun 24, 79 Pompeii, Italy, Roman Empire 79 Rome Sunday Sep 14, 81 Rome Tuesday Sep 18, 96 Roman EmpireNerva

Rome Tuesday Sep 18, 96 On 18 September 96, Domitian was assassinated in a palace conspiracy involving members of the Praetorian Guard and several of his freedmen. On the same day, Nerva was declared emperor by the Roman Senate. As the new ruler of the Roman Empire, he vowed to restore liberties that had been curtailed during the autocratic government of Domitian.

Rome 97 Roman EmpireNerva adopted Trajan

Rome 97 Nerva's brief reign was marred by financial difficulties and his inability to assert his authority over the Roman army. A revolt by the Praetorian Guard in October 97 essentially forced him to adopt an heir. After some deliberation, Nerva adopted Trajan, a young and popular general, as his successor.

Gardens of Sallust, Rome, Italy, Roman Empire Monday Jan 27, 98 Rome 105 Rome, Roman Empire 113 LibrariesUlpian Library

Rome, Roman Empire 113 One of the best preserved was the ancient Ulpian Library built by the Emperor Trajan. Completed in 112/113 AD, the Ulpian Library was part of Trajan's Forum built on the Capitoline Hill. Trajan's Column separated the Greek and Latin rooms which faced each other. The structure was approximately fifty feet high with the peak of the roof reaching almost seventy feet.

Roman Empire 117 Roman Empire Wednesday Aug 11, 117 Roman Empire 117 Roman EmpireFour executions

Roman Empire 117 Hadrian relieved Judea's governor, the outstanding Moorish general Lusius Quietus, of his personal guard of Moorish auxiliaries; then he moved on to quell disturbances along the Danube frontier. There was no public trial for the four – they were tried in absentia, hunted down, and killed. Hadrian claimed that Attianus had acted on his own initiative, and rewarded him with senatorial status and consular rank; then pensioned him off, no later than 120. Hadrian assured the senate that henceforth their ancient right to prosecute and judge their own would be respected. In Rome, Hadrian's former guardian and current Praetorian Prefect, Attianus, claimed to have uncovered a conspiracy involving Lusius Quietus and three other leading senators, Lucius Publilius Celsus, Aulus Cornelius Palma Frontonianus, and Gaius Avidius Nigrinus.

Roman Empire 120 Roman Empire 125 Roman Empire Tuesday Feb 25, 138 Roman EmpireAntoninus Pius "adopted son"

Roman Empire Tuesday Feb 25, 138 Antoninus Pius acquired much favor with Hadrian, who adopted him as his son and successor on 25 February 138, after the death of his first adopted son Lucius Aelius, on the condition that Antoninus would, in turn, adopt Marcus Annius Verus, the son of his wife's brother, and Lucius, son of Lucius Aelius, who afterward became the emperors, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Roman Empire Friday Jul 11, 138 Roman Empire 140 United Kingdom 142 Roman EmpireConstruction began of Antonine Wall

United Kingdom 142 It was however in Britain that Antoninus decided to follow a new, more aggressive path, with the appointment of a new governor in 139, Quintus Lollius Urbicus, a native of Numidia and previously governor of Germania Inferior as well as a new man. Under instructions from the emperor, Lollius undertook an invasion of southern Scotland, winning some significant victories, and constructing the Antonine Wall from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde. The wall, however, was soon gradually decommissioned during the mid-150s and eventually abandoned late during the reign (early 160s), for reasons that are still not quite clear.

Lorium, Etruria, Italy, Roman Empire Saturday Mar 7, 161 Rome Saturday Mar 7, 161 Roman EmpireMarcus Aurelius

Rome Saturday Mar 7, 161 Marcus was effectively the sole ruler of the Empire. The formalities of the position would follow. The senate would soon grant him the name Augustus and the title imperator, and he would soon be formally elected as Pontifex Maximus, chief priest of the official cults. Marcus made some show of resistance: the biographer writes that he was 'compelled' to take imperial power.

Roman Empire 161 Roman Empire 2nd Century Disasters with highest death tollsAntonine Plague

Roman Empire 2nd Century The Antonine Plague of 165 to 180 AD, also known as the Plague of Galen (from the name of the Greek physician living in the Roman Empire who described it), was an ancient pandemic brought back to the Roman Empire by troops returning from campaigns in the Near East. The disease broke out again nine years later, according to the Roman historian Dio Cassius (155–235), causing up to 2,000 deaths a day in Rome, one quarter of those who were affected, giving the disease a mortality rate of about 25%. The total deaths have been estimated at five million, and the disease killed as much as one-third of the population in some areas and devastated the Roman army.

Altinum, Italy, Roman Empire 169 Roman EmpireLucius Verus died

Altinum, Italy, Roman Empire 169 In the spring of 168 war broke out on the Danubian border when the Marcomanni invaded the Roman territory. This war would last until 180, but Verus did not see the end of it. In 168, as Verus and Marcus Aurelius returned to Rome from the field, Verus fell ill with symptoms attributed to food poisoning, dying after a few days (169).

Roman Empire 179 Rome, Roman Empire 182 Roman EmpireAssassination attempt (Commodus)

Rome, Roman Empire 182 The first crisis of the reign came in 182 when Lucilla engineered a conspiracy against her brother. Her motive is alleged to have been the envy of Empress Crispina. Her husband, Pompeianus, was not involved, but two men alleged to have been her lovers, Marcus Ummidius Quadratus Annianus (the consul of 167, who was also her first cousin) and Appius Claudius Quintianus, attempted to murder Commodus as he entered a theater. They bungled the job and were seized by the emperor's bodyguard.

Rome, Roman Empire Monday Dec 31, 192 Rome, Roman Empire Thursday Mar 28, 193 Roman EmpirePertinax died

Rome, Roman Empire Thursday Mar 28, 193 On 28 March 193, Pertinax was at his palace when a contingent of some three hundred soldiers of the Praetorian Guard rushed the gates (two hundred according to Cassius Dio). Sources suggest that they had received only half their promised pay. Neither the guards on duty nor the palace officials chose to resist them. Pertinax sent Laetus to meet them, but he chose to side with the insurgents instead and deserted the emperor.

Rome 193 Roman EmpireThrone was to be sold

Rome 193 After the murder of Pertinax on 28 March 193, the Praetorian guard announced that the throne was to be sold to the man who would pay the highest price. Titus Flavius Claudius Sulpicianus, prefect of Rome and Pertinax's father-in-law, who was in the Praetorian camp ostensibly to calm the troops, began making offers for the throne. Meanwhile, Julianus also arrived at the camp, and since his entrance was barred, shouted out offers to the guard. After hours of bidding, Sulpicianus promised 20,000 sesterces to every soldier; Julianus, fearing that Sulpicianus would gain the throne, then offered 25,000. The guards closed with the offer of Julianus, threw open the gates, and proclaimed him emperor. Threatened by the military, the senate also declared him emperor. His wife and his daughter both received the title Augusta.

Rome Thursday Mar 28, 193 Roman EmpireDidius Julianus

Rome Thursday Mar 28, 193 Because Julianus bought his position rather than acquiring it conventionally through succession or conquest, he was a deeply unpopular emperor. When Julianus appeared in public, he frequently was greeted with groans and shouts of "robber and parricide." Once, a mob even obstructed his progress to the Capitol by pelting him with large stones.

Rome Sunday Jun 2, 193 Rome Tuesday Dec 17, 211 Roman EmpireCaracalla tried unsuccessfully to murder Geta

Rome Tuesday Dec 17, 211 The current stability of their joint government was only through the mediation and leadership of their mother, Julia Domna, accompanied by other senior courtiers and generals in the military. The historian Herodian asserted that the brothers decided to split the empire into two halves, but with the strong opposition of their mother, the idea was rejected, when, by the end of 211, the situation had become unbearable. Caracalla tried unsuccessfully to murder Geta during the festival of Saturnalia (17 December).

Rome Thursday Dec 26, 211 Rome Friday Apr 11, 217 Roman EmpireMacrinus was declared augustus

Rome Friday Apr 11, 217 On April 8, 217, Caracalla was assassinated traveling to Carrhae. Three days later, Macrinus was declared Augustus. Diadumenian was the son of Macrinus, born in 208. He was given the title Caesar in 217, when his father became augustus, and raised to co-Augustus the following year.

Rome Wednesday Mar 6, 222 Roman EmpireA romur

Rome Wednesday Mar 6, 222 Alexander Severus was adopted as son and caesar by his slightly older and very unpopular cousin, the emperor Elagabalus at the urging of the influential and powerful Julia Maesa — who was the grandmother of both cousins and who had arranged for the emperor's acclamation by the Third Legion. On March 6, 222, when Alexander was just fourteen, a rumor went around the city troops that Alexander had been killed, triggering a revolt of the guards that had sworn his safety from Elegabalus and his accession as emperor.

Rome Wednesday Mar 13, 222 Roman EmpireSeverus Alexander

Rome Wednesday Mar 13, 222 The running of the Empire during this time was mainly left to his grandmother and mother (Julia Soaemias). Seeing that her grandson's outrageous behavior could mean the loss of power, Julia Maesa persuaded Elagabalus to accept his cousin Alexander Severus as caesar (and thus the nominal emperor-to-be). However, Alexander was popular with the troops, who viewed their new emperor with dislike: when Elagabalus, jealous of this popularity, removed the title of caesar from his nephew, the enraged Praetorian Guard swore to protect him. Elagabalus and his mother were murdered in a Praetorian Guard camp mutiny.

Terni, Italy 226 Rome, Italy 3rd Century Valentine's DayThe legend of Saint Valentine

Rome, Italy 3rd Century Another legend is that Valentine refused to sacrifice to pagan gods. Being imprisoned for this, Valentine gave his testimony in prison and through his prayers healed the jailer's daughter who was suffering from blindness. On the day of his execution, he left her a note that was signed, "Your Valentine". there are two possible figures behind the character of Saint Valentine Saint Valantine of Rome and Saint Valentine of Terni.

Rome Sunday Mar 22, 235 Roman Empire 3rd Century Byzantine EmpireCrisis of the Third Century

Roman Empire 3rd Century The Roman army succeeded in conquering many territories covering the Mediterranean region and coastal regions in southwestern Europe and North Africa. These territories were home to many different cultural groups, both urban populations, and rural populations. The West also suffered more heavily from the instability of the 3rd century. This distinction between the established Hellenised East and the younger Latinised West persisted and became increasingly important in later centuries, leading to a gradual estrangement of the two worlds.

Rome Mar, 238 Roman EmpireGordian I proclaim himself emperor

Rome Mar, 238 Some young aristocrats in Africa murdered the imperial tax-collector then approached the regional governor, Gordian, and insisted that he proclaim himself emperor. Gordian agreed reluctantly, but as he was almost 80 years old, he decided to make his son joint emperor, with equal power. The Senate recognized father and son as emperors Gordian I and Gordian II, respectively. Their reign, however, lasted for only 20 days. Capelianus, the governor of the neighboring province of Numidia, held a grudge against the Gordians. He led an army to fight them and defeated them decisively at Carthage. Gordian II was killed in the battle, and on hearing this news, Gordian I hanged himself. Gordian I and II were deified by the senate.

Rome Sunday Apr 22, 238 Roman EmpirePupienus and Balbinus joint emperors

Rome Sunday Apr 22, 238 Meanwhile, Maximinus, now declared a public enemy, had already begun to march on Rome with another army. The senate's previous candidates, the Gordians, had failed to defeat him, and knowing that they stood to die if he succeeded, the senate needed a new emperor to defeat him. With no other candidates in view, on 22 April 238, they elected two elderly senators, Pupienus and Balbinus (who had both been part of a special senatorial commission to deal with Maximinus), as joint emperors. Therefore, Marcus Antonius Gordianus Pius, the thirteen-year-old grandson of Gordian I, was nominated as emperor Gordian III, holding power only nominally in order to appease the population of the capital, which was still loyal to the Gordian family.

Aquileia, Italy, Roman Empire Thursday May 10, 238 Rome Sunday Jul 29, 238 Roman EmpireGordian III was proclaimed sole emperor

Rome Sunday Jul 29, 238 The situation for Pupienus and Balbinus, despite Maximinus' death, was doomed from the start with popular riots, military discontent and enormous fire that consumed Rome in June 238. On July 29, Pupienus and Balbinus were killed by the Praetorian Guard and Gordian was proclaimed sole emperor.

Rome Feb, 244 Verona, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 249 Roman EmpirePhilip was killed

Verona, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 249 Although Decius tried to come to terms with Philip, Philip's army met the usurper near modern Verona that summer. Decius easily won the battle and Philip was killed sometime in September 249, either in the fighting or assassinated by his own soldiers who were eager to please the new ruler. Philip's eleven-year-old son and heir may have been killed with his father and Priscus disappeared without a trace.

Italy 250 Rome Jun, 251 Roman EmpireTrebonianus Gallus

Rome Jun, 251 In June 251, Decius and his co-emperor and son Herennius Etruscus died in the Battle of Abrittus at the hands of the Goths they were supposed to punish for raids into the empire. According to rumors supported by Dexippus (a contemporary Greek historian) and the thirteenth Sibylline Oracle, Decius' failure was largely owing to Gallus, who had conspired with the invaders. In any case, when the army heard the news, the soldiers proclaimed Gallus emperor, despite Hostilian, Decius' surviving son, ascending the imperial throne in Rome. This action of the army, and the fact that Gallus seems to have been on good terms with Decius' family, makes Dexippus' allegation improbable. Gallus did not back down from his intention to become emperor, but accepted Hostilian as co-emperor, perhaps to avoid the damage of another civil war.

Interamna (Present-Day Terni, Italy) Aug, 253 Roman EmpireGallus was killed

Interamna (Present-Day Terni, Italy) Aug, 253 Since the army was no longer pleased with the Emperor, the soldiers proclaimed Aemilianus emperor. With a usurper, supported by Pauloctus, threatening the throne, Gallus prepared for a fight. He recalled several legions and ordered reinforcements to return to Rome from Gaul under the command of the future emperor Publius Licinius Valerianus. Despite these dispositions, Aemilianus marched onto Italy ready to fight for his claim and caught Gallus at Interamna (modern Terni) before the arrival of Valerianus. What exactly happened is not clear. Later sources claim that after an initial defeat, Gallus and Volusianus were murdered by their own troops; or Gallus did not have the chance to face Aemilianus at all because his army went over to the usurper. In any case, both Gallus and Volusianus were killed in August 253.

Rome 253 Roman EmpireMarcus Aemilius Aemilianus "Aemilian"

Rome 253 Aemilian continued towards Rome. The Roman senate, after a short opposition, decided to recognize him as emperor. According to some sources, Aemilian then wrote to the Senate, promising to fight for the Empire in Thrace and against Persia and to relinquish his power to the Senate, of which he considered himself a general.

Spoletium, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 253 Roman EmpireAemilian died

Spoletium, Italy, Roman Empire Sep, 253 Valerian, governor of the Rhine provinces, was on his way south with an army which, according to Zosimus, had been called in as reinforcement by Gallus. But modern historians believe this army, possibly mobilized for an incumbent campaign in the East, moved only after Gallus' death to support Valerian's bid for power. Emperor Aemilian's men, fearful of civil war and Valerian's larger force, mutinied. They killed Aemilian at Spoletium or at the Sanguinarium bridge, between Oriculum and Narnia (halfway between Spoletium and Rome), and recognized Valerian as the new emperor.

Rome Saturday Oct 22, 253 Roman EmpireValerian's first act as emperor

Rome Saturday Oct 22, 253 Valerian's first act as emperor on October 22, 253, was to appoint his son Gallienus caesar. Early in his reign, affairs in Europe went from bad to worse, and the whole West fell into disorder. In the East, Antioch had fallen into the hands of a Sassanid vassal and Armenia was occupied by Shapur I (Sapor).

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 268 Roman EmpireGallienus was challenged by Aureolus

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 268 In 268, at some time before or soon after the battle of Naissus, the authority of Gallienus was challenged by Aureolus, commander of the cavalry stationed in Mediolanum (Milan), who was supposed to keep an eye on Postumus. Instead, he acted as deputy to Postumus until the very last days of his revolt, when he seems to have claimed the throne for himself. The decisive battle took place at what is now Pontirolo Nuovo near Milan; Aureolus was clearly defeated and driven back to Milan. Gallienus laid siege to the city but was murdered during the siege. There are differing accounts of the murder, but the sources agree that most of Gallienus' officials wanted him dead.

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Sep, 268 Roman EmpireGallienus died

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Sep, 268 Cecropius, commander of the Dalmatians, spread the word that the forces of Aureolus were leaving the city, and Gallienus left his tent without his bodyguard, only to be struck down by Cecropius. According to Aurelius Victor and Zonaras, on hearing the news that Gallienus was dead, the Senate in Rome ordered the execution of his family (including his brother Valerianus and son Marinianus) and their supporters, just before receiving a message from Claudius to spare their lives and deify his predecessor.

Rome Sep, 268 Roman EmpireClaudius Gothicus was chosen by the army

Rome Sep, 268 Whichever story is true, Gallienus was killed in the summer of 268, and Claudius was chosen by the army outside of Milan to succeed him. Accounts tell of people hearing the news of the new emperor and reacting by murdering Gallienus' family members until Claudius declared he would respect the memory of his predecessor. Claudius had the deceased emperor deified and buried in a family tomb on the Appian Way. The traitor Aureolus was not treated with the same reverence, as he was killed by his besiegers after a failed attempt to surrender.

Rome, Italy Tuesday Feb 16, 269 Rome 270 Roman EmpireQuintillus

Rome 270 Quintillus was declared emperor either by the Senate or by his brother's soldiers upon the latter's death in 270. Eutropius reports Quintillus to have been elected by soldiers of the Roman army immediately following the death of his brother; the choice was reportedly approved by the Roman Senate.

Aquileia, Italy, Roman Empire 270 Roman EmpireQuintillus death

Aquileia, Italy, Roman Empire 270 The few records of Quintillus' reign are contradictory. They disagree on the length of his reign, variously reported to have lasted as few as 17 days and as many as 177 days (about six months). Records also disagree on the cause of his death.

Northern Italy 270 Roman EmpireAurelian campaigned in northern Italia

Northern Italy 270 The first actions of the new Emperor were aimed at strengthening his own position in his territories. Late in 270, Aurelian campaigned in northern Italia against the Vandals, Juthungi, and Sarmatians, expelling them from Roman territory. To celebrate these victories, Aurelian was granted the title of Germanicus Maximus.

Roman Empire 272 Roman EmpireAurelian turned his attention to the lost eastern provinces of the empire

Roman Empire 272 In 272, Aurelian turned his attention to the lost eastern provinces of the empire, the Palmyrene Empire, ruled by Queen Zenobia from the city of Palmyra. Zenobia had carved out her own empire, encompassing Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and large parts of Asia Minor. The Syrian queen cut off Rome's shipments of grain, and in a matter of weeks, the Romans started running low on bread. In the beginning, Aurelian had been recognized as Emperor, while Vaballathus, the son of Zenobia, held the title of rex and imperator ("king" and "supreme military commander"), but Aurelian decided to invade the eastern provinces as soon as he felt his army to be strong enough.

Rome 272 Roman EmpireAurelian is believed to have terminated Trajan's alimenta program

Rome 272 Aurelian is believed to have terminated Trajan's alimenta program. Roman prefect Titus Flavius Postumius Quietus was the last known official in charge of the alimenta, in 272 AD. If Aurelian "did suppress this food distribution system, he most likely intended to put into effect a more radical reform."

Rome 274 Roman EmpireAurelian turned his attention to the west and the Gallic Empire

Rome 274 In 274, the victorious emperor turned his attention to the west and the Gallic Empire which had already been reduced in size by Claudius II. Aurelian won this campaign largely through diplomacy; the "Gallic Emperor" Tetricus was willing to abandon his throne and allow Gaul and Britain to return to the Empire, but could not openly submit to Aurelian. Instead, the two seem to have conspired so that when the armies met at Châlons-en-Champagne that autumn, Tetricus simply deserted to the Roman camp and Aurelian easily defeated the Gallic army facing him. Tetricus was rewarded for his part in the conspiracy with a high-ranking position in Italy itself.

Rome Friday Dec 25, 274 Roman EmpireTemple of the Sun

Rome Friday Dec 25, 274 Aurelian strengthened the position of the Sun god Sol Invictus as the main divinity of the Roman pantheon. His intention was to give to all the peoples of the Empire, civilians or soldiers, easterners or westerners, a single god they could believe in without betraying their own gods. The centre of the cult was a new temple, built in 274 and dedicated on December 25 of that year in the Campus Agrippae in Rome, with great decorations financed by the spoils of the Palmyrene Empire.

Roman Empire 275 Roman EmpireAurelian set out for another campaign against the Sassanids

Roman Empire 275 The deaths of the Sassanid Kings Shapur I (272) and Hormizd I (273) in quick succession, and the rise to power of a weakened ruler (Bahram I), presented an opportunity to attack the Sassanid Empire, and in 275 Aurelian set out for another campaign against the Sassanids. On his way, he suppressed a revolt in Gaul—possibly against Faustinus, an officer or usurper of Tetricus—and defeated barbarian marauders in Vindelicia (Germany).

Roman Empire Saturday Sep 25, 275 Roman Empire 270s Roman Empire Jul, 276 Rome 276 Roman EmpireProbus

Rome 276 Florian, the half-brother of Tacitus, also proclaimed himself emperor, and took control of Tacitus' army in Asia Minor, but was killed by his own soldiers after an indecisive campaign against Probus in the mountains of Cilicia. In contrast to Florian, who ignored the wishes of the senate, Probus referred his claim to Rome in a respectful dispatch. The senate enthusiastically ratified his pretensions.

Rome 280s Roman EmpireTime of peace

Rome 280s The army discipline which Aurelian had repaired was cultivated and extended under Probus, who was however more shy in the practice of cruelty. One of his principles was never to allow the soldiers to be idle, and to employ them in time of peace on useful works, such as the planting of vineyards in Gaul, Pannonia, and other districts, in order to restart the economy in these devastated lands.

Roman Empire 283 Roman EmpireMarcus Aurelius Carinus

Roman Empire 283 After the death of Emperor Probus in a spontaneous mutiny of the army in 282, his praetorian prefect, Carus, ascended to the throne. The latter, upon his departure for the Persian war, elevated his two sons to the title of Caesar. Carinus, the elder, was left to handle the affairs of the west in his absence, while the younger, Numerian, accompanied his father to the east.

Roman Empire 285 Roman EmpireDiocletian

Roman Empire 285 Diocletian may have become involved in battles against the Quadi and Marcomanni immediately after the Battle of the Margus. He eventually made his way to northern Italy and made an imperial government, but it is not known whether he visited the city of Rome at this time.

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Thursday Jul 30, 285 Roman EmpireDiocletian raised his fellow-officer Maximian to a co-emperor

Mediolanum (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Thursday Jul 30, 285 Conflict boiled in every province, from Gaul to Syria, Egypt to the lower Danube. It was too much for one person to control, and Diocletian needed a lieutenant. At some time in 285 at Mediolanum (Milan), Diocletian raised his fellow-officer Maximian to the office of caesar, making him co-emperor.

Roman Empire Thursday Apr 1, 286 Roman EmpireMaximian took up the title of Augustus

Roman Empire Thursday Apr 1, 286 Spurred by the crisis, on 1 April 286, Maximian took up the title of Augustus. His appointment is unusual in that it was impossible for Diocletian to have been present to witness the event. It has even been suggested that Maximian usurped the title and was only later recognized by Diocletian in hopes of avoiding civil war.

Milan, Italy Dec, 290 Roman EmpireDiocletian met Maximian in Milan

Milan, Italy Dec, 290 Diocletian met Maximian in Milan in the winter of 290–91, either in late December 290 or January 291. The meeting was undertaken with a sense of solemn pageantry. The emperors spent most of their time in public appearances. It has been surmised that the ceremonies were arranged to demonstrate Diocletian's continuing support for his faltering colleague.

Milan, Italy Wednesday Mar 1, 293 Roman EmpireMaximian gave Constantius the office of caesar

Milan, Italy Wednesday Mar 1, 293 Sometime after his return, and before 293, Diocletian transferred command of the war against Carausius from Maximian to Flavius Constantius, a former Governor of Dalmatia and a man of military experience stretching back to Aurelian's campaigns against Zenobia (272–73). He was Maximian's praetorian prefect in Gaul, and the husband to Maximian's daughter, Theodora. On 1 March 293 at Milan, Maximian gave Constantius the office of caesar.

Roman Empire 293 Byzantine EmpireThe Tetrarchy systems

Roman Empire 293 An early instance of the partition of the Empire into East and West occurred in 293 when Emperor Diocletian created a new administrative system (the tetrarchy), to guarantee security in all endangered regions of his Empire. He associated himself with a co-emperor (Augustus), and each co-emperor then adopted a young colleague given the title of Caesar, to share in their rule and eventually to succeed the senior partner. Each tetrarch was in charge of a part of the Empire.

Roman Empire 305 Roman Empire Wednesday Nov 11, 308 Roman EmpireGalerius appoint Licinius to be Augustus in place of Severus

Roman Empire Wednesday Nov 11, 308 Galerius assumed the consular fasces in 308 with Diocletian as his colleague. In the autumn of 308, Galerius again conferred with Diocletian at Carnuntum (Petronell-Carnuntum, Austria). Diocletian and Maximian were both present on 11 November 308, to see Galerius appoint Licinius to be Augustus in place of Severus, who had died at the hands of Maxentius.

Mediolanum, Roman Empire (Present-Day Milan, Italy) Mar, 313 Mediolanum, Roman Empire (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 313 Roman EmpireEdict of Milan

Mediolanum, Roman Empire (Present-Day Milan, Italy) 313 The Edict of Milan was the February AD 313 agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and Emperor Licinius, who controlled the Balkans, met in Mediolanum (modern-day Milan) and, among other things, agreed to change policies towards Christians following the edict of toleration issued by Emperor Galerius two years earlier in Serdica. The Edict of Milan gave Christianity legal status and a reprieve from persecution but did not make it the state church of the Roman Empire. That occurred in AD 380 with the Edict of Thessalonica.

Rome, Roman Empire 313 Roman Empire 313 Roman EmpireTetrarchy was replaced by a system of two emperors

Roman Empire 313 Given that Constantine had already crushed his rival Maxentius in 312, the two men decided to divide the Roman world between them. As a result of this settlement, the Tetrarchy was replaced by a system of two emperors, called Augusti: Licinius became Augustus of the East, while his brother-in-law, Constantine, became Augustus of the West. After making the pact, Licinius rushed immediately to the East to deal with another threat, an invasion by the Persian Sassanid Empire.

Eastern Roman EmpireI "Italy" 395