One week later, the House adopted eleven articles of impeachment against the president.

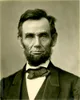

Following Union Army victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in July 1863, President Lincoln began contemplating the issue of how to bring the South back into the Union.

The forgiving tone of the president's plan, plus the fact that he implemented it by presidential directive without consulting Congress, incensed Radical Republicans, who countered with a more stringent plan.

Their proposal for Southern reconstruction, the Wade–Davis Bill, passed both houses of Congress in July 1864, but was pocket vetoed by the president and never took effect.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865, just days after the Army of Northern Virginia's surrender at Appomattox briefly lessened the tension over who would set the terms of peace.

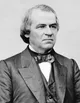

The radicals, while suspicious of the new president and his policies, believed, based upon his record, that Andrew Johnson would defer, or at least acquiesce to their hardline proposals.

Then after several states left the Union, including his own, he chose to stay in Washington (rather than resign his U.S. Senate seat), and later, when Union troops occupied Tennessee, Johnson was appointed military governor. While in that position he had exercised his powers with vigor, frequently stating that "treason must be made odious and traitors punished".

In February 1866, Johnson vetoed legislation extending the Freedmen's Bureau and expanding its powers; Congress was unable to override the veto. Afterward, Johnson denounced Radical Republicans Representative Thaddeus Stevens and Senator Charles Sumner, along with abolitionist Wendell Phillips, as traitors.

Johnson vetoed a Civil Rights Act and a second Freedmen's Bureau bill; the Senate and the House each mustered the two-thirds majorities necessary to override both vetoes, setting the stage for a showdown between Congress and the president.

At an impasse with Congress, Johnson offered himself directly to the American public as a "tribune of the people".

In the late-summer of 1866, the president embarked on a national "Swing Around the Circle" speaking tour, where he asked his audiences for their support in his battle against the Congress and urged voters to elect representatives to Congress in the upcoming midterm election who supported his policies.

The primary charge against Johnson was violation of the Tenure of Office Act, passed by Congress in March 1867, over his veto.

Because the Tenure of Office Act did permit the president to suspend such officials when Congress was out of session, when Johnson failed to obtain Stanton's resignation, he instead suspended Stanton on August 5, 1867, which gave him the opportunity to appoint General Ulysses S. Grant, then serving as Commanding General of the Army, interim Secretary of War.

To ensure that Stanton would not be replaced, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867 over Johnson's veto. The act required the President to seek the Senate's advice and consent before relieving or dismissing any member of his Cabinet (an indirect reference to Stanton) or, indeed, any federal official whose initial appointment had previously required its advice and consent.

When the Senate adopted a resolution of non-concurrence with Stanton's dismissal in December 1867, Grant told Johnson he was going to resign, fearing punitive legal action. Johnson assured Grant that he would assume all responsibility in the matter, and asked him to delay his resignation until a suitable replacement could be found.

Contrary to Johnson's belief that Grant had agreed to remain in office, when the Senate voted and reinstated Stanton in January 1868, Grant immediately resigned, before the president had an opportunity to appoint a replacement.

Johnson's opponents in Congress were outraged by his actions; the president's challenge to congressional authority—with regard to both the Tenure of Office Act and post-war reconstruction—had, in their estimation, been tolerated for long enough.

On February 21, 1868, the president appointed Lorenzo Thomas, a brevet major general in the Army, as interim Secretary of War. Johnson thereupon informed the Senate of his decision.

Expressing the widespread sentiment among House Republicans, Representative William D. Kelley (on February 22, 1868) declared:

Sir, the bloody and untilled fields of the ten unreconstructed states, the unsheeted ghosts of the two thousand murdered negroes in Texas, cry, if the dead ever evoke vengeance, for the punishment of Andrew Johnson.

On February 24, 1868, three days after Johnson's dismissal of Stanton, the House of Representatives voted 126 to 47 (with 17 members not voting) in favor of a resolution to impeach the president for high crimes and misdemeanors.

The impeachment of Andrew Johnson was initiated on February 24, 1868, when the United States House of Representatives resolved to impeach Andrew Johnson, 17th president of the United States, for "high crimes and misdemeanors", which were detailed in eleven articles of impeachment.

On March 4, 1868, amid tremendous public attention and press coverage, the eleven Articles of Impeachment were presented to the Senate, which reconvened the following day as a court of impeachment, with Chief Justice Salmon Chase presiding, and proceeded to develop a set of rules for the trial and its officers.

Johnson was furious at Grant, accusing him of lying during a stormy cabinet meeting. The March 1868 publication of several angry messages between Johnson and Grant led to a complete break between the two. As a result of these letters, Grant solidified his standing as the frontrunner for the 1868 Republican presidential nomination.

The trial was conducted mostly in open session, and the Senate chamber galleries were filled to capacity throughout. Public interest was so great that the Senate issued admission passes for the first time in its history. For each day of the trial, 1,000 color coded tickets were printed, granting admittance for a single day.

The House impeachment committee was made up of: John Bingham, George S. Boutwell, Benjamin Butler, John A. Logan, Thaddeus Stevens, James F. Wilson, and Thomas Williams. The president's defense team was made up of Henry Stanbery, William M. Evarts, Benjamin R. Curtis, Thomas A. R. Nelson and William S. Groesbeck. On the advice of counsel, the president did not appear at the trial.

On the first day, Johnson's defense committee asked for 40 days to collect evidence and witnesses since the prosecution had had a longer amount of time to do so, but only 10 days were granted. The proceedings began on March 23.

After the charges against the president were made, Henry Stanbery asked for another 30 days to assemble evidence and summon witnesses, saying that in the 10 days previously granted there had only been enough time to prepare the president's reply.

John A. Logan argued that the trial should begin immediately and that Stanbery was only trying to stall for time. The request was turned down in a vote 41 to 12. However, the Senate voted the next day to give the defense six more days to prepare evidence, which was accepted

For days Butler spoke out against Johnson's violations of the Tenure of Office Act and further charged that the president had issued orders directly to Army officers without sending them through General Grant. The defense argued that Johnson had not violated the Tenure of Office Act because President Lincoln did not reappoint Stanton as Secretary of War at the beginning of his second term in 1865 and that he was therefore a leftover appointment from the 1860 cabinet, which removed his protection by the Tenure of Office Act.

The prosecution called several witnesses in the course of the proceedings until April 9, when they rested their case.

Benjamin Curtis called attention to the fact that after the House passed the Tenure of Office Act, the Senate had amended it, meaning that it had to return it to a Senate–House conference committee to resolve the differences. He followed up by quoting the minutes of those meetings, which revealed that while the House members made no notes about the fact, their sole purpose was to keep Stanton in office, and the Senate had disagreed.

The next witness was General William T. Sherman, who testified that President Johnson had offered to appoint Sherman to succeed Stanton as Secretary of War in order to ensure that the department was effectively administered.

Sherman essentially affirmed that Johnson only wanted him to manage the department and not to execute directions to the military that would be contrary to the will of Congress.

The defense then called their first witness, Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas. He did not provide adequate information in the defense's cause and Butler made attempts to use his information to the prosecution's advantage.

The first vote was taken on May 16 for the eleventh article. Prior to the vote, Samuel Pomeroy, the senior senator from Kansas, told the junior Kansas Senator Ross that if Ross voted for acquittal that Ross would become the subject of an investigation for bribery. Afterward, in hopes of persuading at least one senator who voted not guilty to change his vote, the Senate adjourned for 10 days before continuing voting on the other articles.

All republicans voted guilty (35 Votes), the majority of democrats also voted guilty (10 votes) and 9 democrats voted not guilty on Article XI.

During the hiatus, under Butler's leadership, the House put through a resolution to investigate alleged "improper or corrupt means used to influence the determination of the Senate". Despite the Radical Republican leadership's heavy-handed efforts to change the outcome, when votes were cast on May 26 for the second and third articles, the results were the same as the first.

All republicans voted guilty (35 Votes), the majority of democrats also voted guilty (10 votes) and 9 democrats voted not guilty on Article III.

All republicans voted guilty (35 Votes), the majority of democrats also voted guilty (10 votes) and 9 democrats voted not guilty on Article II.

Johnson complained about Stanton's restoration to office and searched desperately for someone to replace Stanton who would be acceptable to the Senate. He first proposed the position to General William Tecumseh Sherman, an enemy of Stanton, who turned down his offer.

Thomas personally delivered the president's dismissal notice to Stanton, who rejected the legitimacy of the decision. Rather than vacate his office, Stanton barricaded himself in there and ordered Thomas arrested for violating the Tenure of Office Act. He also informed Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax and President pro tempore of the Senate Benjamin Wade of the situation.

At its conclusion, senators voted on three of the articles of impeachment. On each occasion the vote was 35–19, with 35 senators voting guilty and 19 not guilty. As the constitutional threshold for a conviction in an impeachment trial is a two-thirds majority guilty vote, 36 votes in this instance, Johnson was not convicted. He remained in office through the end of his term the following March 4, though as a lame duck without influence on public policy.

After the trial, Butler conducted hearings on the widespread reports that Republican senators had been bribed to vote for Johnson's acquittal. In Butler's hearings, and in subsequent inquiries, there was increasing evidence that some acquittal votes were acquired by promises of patronage jobs and cash cards. Political deals were struck as well.

Moreover, there is evidence that the prosecution attempted to bribe the senators voting for acquittal to switch their votes to conviction. Maine Senator Fessenden was offered the Ministership to Great Britain.

Butler's investigation also boomeranged when it was discovered that Kansas Senator Pomeroy, who voted for conviction, had written a letter to Johnson's Postmaster General seeking a $40,000 bribe for Pomeroy's acquittal vote along with three or four others in his caucus.

Butler was himself told by Wade that Wade would appoint Butler as Secretary of State when Wade assumed the Presidency after a Johnson conviction.

In 1887, the Tenure of Office Act was repealed by Congress, and subsequent rulings by the United States Supreme Court seemed to support Johnson's position that he was entitled to fire Stanton without Congressional approval.