The Teamsters union, founded in 1903.

Hoffa was born in Brazil, Indiana, on February 14, 1913, to John and Viola (née Riddle) Hoffa.

His father, who was of German descent (now referred to as Pennsylvania Dutch ancestry), died in 1920 from lung disease when Hoffa was seven years old.

The family moved to Detroit in 1924, where Hoffa was raised and lived the rest of his life.

Hoffa left school at age 14 and began working full-time manual labor jobs such as house painting to help support his family.

Hoffa began union organizational work at the grassroots level through his employment as a teenager with a grocery chain, a job which paid substandard wages and offered poor working conditions with minimal job security. The workers were displeased with this situation and tried to organize a union to better their lot. Although Hoffa was young, his courage and approachability in this role impressed fellow workers, and he rose to a leadership position.

The Teamsters organized truck drivers and warehousemen, first throughout the Midwest, then nationwide. Hoffa played a major role in the union's skillful use of "quickie strikes", secondary boycotts, and other means of leveraging union strength at one company, to then move to organize workers, and finally to win contract demands at other companies. This process, which took several years starting in the early 1930s, eventually brought the Teamsters to a position of being one of the most powerful unions in the United States.

Hoffa worked to defend the Teamsters unions from raids by other unions, including the CIO, and extended the Teamsters' influence in the Midwestern states from the late 1930s to the late 1940s.

By 1932, after defiantly refusing to work for an abusive shift foreman, who inspired Hoffa's long career of organizing workers, he left the grocery chain, in part because of his union activities. Hoffa was then invited to become an organizer with the Local 299 of the Teamsters in Detroit.

The Teamsters union had 75,000 members in 1933.

Hoffa married Josephine Poszywak, an 18-year-old Detroit laundry worker of Polish heritage, in Bowling Green, Ohio, on September 24, 1936; the couple had met during a non-unionized laundry workers' strike action six months earlier.

As a result of Hoffa's work with other union leaders to consolidate local union trucker groups into regional sections, and then into a national body—work that Hoffa ultimately completed over a period of two decades—membership grew to 170,000 members by 1936. Three years later, there were 420,000.

The couple had a daughter, Barbara Ann Crancer in 1938, in Detroit, Michigan.

The Hoffas paid $6,800 in 1939 for a modest home in northwest Detroit.

The couple had a son, James P. Hoffa on May 19, 1941, in Detroit, Michigan.

Although he never actually worked as a truck driver, Hoffa became president of Local 299 in December 1946.

He then rose to lead the combined group of Detroit-area locals shortly afterwards, and advanced to become head of the Michigan Teamsters groups sometime later. During this time, Hoffa obtained a deferment from military service in World War II by successfully making a case for his union leadership skills being of more value to the nation, by keeping freight running smoothly to assist the war effort.

The number grew steadily during World War II and through the post-war boom to top a million members by 1951.

At the 1952 IBT convention in Los Angeles, Hoffa was selected as national vice-president by incoming president Dave Beck, successor to Daniel J. Tobin, who had been president since 1907. Hoffa had quelled an internal revolt against Tobin by securing Central States regional support for Beck at the convention. In exchange, Beck made Hoffa a vice-president.

Hoffa took over the presidency of the Teamsters in 1957, at the convention in Miami Beach, Florida.

Hoffa had first faced major criminal investigations in 1957, as a result of the McClellan Senate hearings. He avoided conviction for several years.

The 1957 AFL–CIO convention, held in Atlantic City, New Jersey, voted by a ratio of nearly five to one to expel the IBT from the larger union group. Vice-President Walter Reuther led the fight to oust the IBT on charges of Hoffa's corrupt leadership.

Hoffa tried to bring the airline workers and other transport employees into the union, with limited success. During this period, he was facing immense personal strain as he was under investigation, on trial, launching appeals of convictions, or imprisoned for virtually all of the 1960s.

Following his re-election as president in 1961, Hoffa worked to expand the union.

Robert Kennedy had been frustrated in earlier attempts to convict Hoffa, while working as counsel to the McClellan subcommittee. As Attorney General from 1961, Kennedy pursued a strong attack on organized crime and he carried on with a so-called "Get Hoffa" squad of prosecutors and investigators.

On March 4, 1964, Hoffa was convicted in Chattanooga, Tennessee, of attempted bribery of a grand juror.

In 1964, he succeeded in bringing virtually all over-the-road truck drivers in North America under a single National Master Freight Agreement, in what may have been his biggest achievement in a lifetime of union activity.

Hoffa was also convicted of fraud later that same year for improper use of the Teamsters' pension fund, in a trial held in Chicago. Hoffa had illegally arranged several large pension fund loans to leading organized crime figures.

Hoffa was re-elected, without opposition, to a third five-year term as president of the IBT, despite having been convicted of jury tampering and mail fraud in court verdicts that were stayed pending review on appeal. Delegates in Miami Beach also elected Frank Fitzsimmons as first vice-president, to become president "if Hoffa has to serve a jail term".

Hoffa began serving his aggregate prison sentence of 13 years (eight years for bribery, five years for fraud) in March 1967 at the Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary in Pennsylvania.

Just before he entered prison, Hoffa appointed Frank Fitzsimmons as acting Teamsters president. Fitzsimmons was a Hoffa loyalist, fellow Detroit resident, and a longtime member of Teamsters Local 299, who owed his own high position in large part to Hoffa's influence.

Despite this, Fitzsimmons soon distanced himself from Hoffa's influence and control after 1967, to Hoffa's displeasure. Fitzsimmons also decentralized power somewhat within the IBT's administration structure, foregoing much of the control Hoffa took advantage of as union president.

Hoffa published a book titled The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa in 1970.

While still in prison, Hoffa resigned as the head of the Teamsters Union, on June 19, 1971.

While Hoffa regained his freedom, the commutation from President Nixon was conditional upon that he cannot "engage in the direct or indirect management of any labor organization" until March 6, 1980.

On December 23, 1971, less than five years into his 13-year sentence, Hoffa was released from prison when President Richard Nixon commuted his sentence to time served.

In 1973 and 1974, Hoffa talked to Anthony Provenzano to ask for help in supporting him for his return to power, but Provenzano refused. Provenzano was a caporegime in the New York City Genovese crime family. At least two of his opponents had been murdered, and others who had spoken out against him had been assaulted.

Hoffa sued to invalidate the non-participation restriction in order to reassert his power over the Teamsters. John Dean, former White House counsel to President Nixon, was among those called upon for depositions in 1974 court proceedings.

Hoffa faced immense resistance to his re-establishment of power from many corners and had lost much of his earlier support, even in the Detroit area. As a result, he intended to begin his comeback at the local level with Local 299 in Detroit, where he retained some influence.

Other Mafia figures who became involved were Anthony Giacalone, an alleged kingpin in the Detroit Mafia, and his younger brother, Vito. The brothers had made three visits to Hoffa's home at Lake Orion and one to the Guardian Building law offices. Their avowed purpose in meeting Hoffa was to set up a "peace meeting" between Provenzano and Hoffa.

On July 30, 1975, Hoffa left home in his green Pontiac Grand Ville at 1:15 p.m. Before heading to the restaurant.

Hoffa disappeared on July 30, 1975, after going out to a meeting with Anthony Provenzano and Anthony Giacalone. The meeting was arranged to take place at 2 p.m. at the Machus Red Fox restaurant in Bloomfield Township, a suburb of Detroit. The Machus Red Fox was known to Hoffa; it had been the site for the wedding reception of his son, James. Hoffa wrote the date in his office calendar: "TG—2 p.m.—Red Fox".

On July 30, 1975, At 2:15 p.m., an annoyed Hoffa called his wife from a payphone on a post in front of Damman Hardware, directly behind the Red Fox and complained, "Where the hell is Tony Giacalone? I'm being stood up." His wife told him she had not heard from anyone. He told her he would be home at 4:00 p.m. Several witnesses saw Hoffa standing by his car and pacing the restaurant's parking lot. Two men saw Hoffa emerge from the Red Fox after a long lunch and recognized him; they stopped to chat with him briefly and to shake his hand.

On July 30, 1975, At 3:27 p.m., Hoffa called Linteau complaining that Giacalone was late. Hoffa said, "That dirty son of a bitch Tony Jocks set this meeting up, and he's an hour and a half late." Linteau told him to calm down and to stop by his office on the way home. Hoffa said he would and hung up; this is Hoffa's last known communication.

On July 30, 1975, Hoffa stopped in Pontiac at the office of his close friend Louis Linteau, a former president of Teamsters Local 614 who now ran a limousine service.

On July 31, 1975, At 7:00 a.m. Hoffa's wife called her son and daughter by telephone, saying their father had not come home.

On July 31, 1975, At 7:20 a.m. Linteau went to the Machus Red Fox and found Hoffa's unlocked car in the parking lot, but there was no sign of Hoffa or any indication of what had happened to him.

On July 31, 1975, At 6:00 p.m., Hoffa's son, James P. Hoffa, filed a missing persons report.

On July 31, 1975, Hoffa's wife called the police, who later arrived at the scene. State police were brought in and the FBI was alerted.

In 1975, Hoffa was working on an autobiography titled Hoffa: The Real Story, which was published a few months after his disappearance.

Hoffa's plans to regain the leadership of the union were met with opposition from some members of the Mafia, including some who were connected to his disappearance in 1975.

After years of investigation, involving numerous law enforcement agencies including the FBI, officials have not reached a definitive conclusion as to Hoffa's fate and who was involved.

In 1978 film F.I.S.T., Sylvester Stallone plays a character based on Hoffa.

Hoffa's wife, Josephine, died on September 12, 1980. She is entombed in Michigan.

Hoffa was declared legally dead on July 30, 1982.

In the 1983 TV miniseries Blood Feud, Hoffa is portrayed by Robert Blake.

In 1989, Kenneth Walton, the Agent-in-Charge of the FBI's Detroit office, told The Detroit News that he knew what had happened to Hoffa. "I'm comfortable I know who did it, but it's never going to be prosecuted because ... we would have to divulge informants, confidential sources."

Author James Ellroy features a fictional historical version of Hoffa in the Underworld USA Trilogy novels as an important secondary character, most prominently in the novels American Tabloid (1995).

James has served as president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT), his father's old position, since 1999.

In 2001, the FBI matched DNA from Hoffa's hair—taken from a brush—with a strand of hair found in a 1975 Mercury Marquis Brougham driven by his friend Charles "Chuckie" O'Brien on July 30, 1975. Police and Hoffa's family had long believed that O'Brien played a role in Hoffa's disappearance. O'Brien had denied being involved in Hoffa's disappearance and that Hoffa had never been a passenger in his car. It was not clear what date Hoffa had been in the car.

Author James Ellroy features a fictional historical version of Hoffa in the Underworld USA Trilogy novels as an important secondary character, most prominently in the novels The Cold Six Thousand (2001).

In the 2003 comedy/drama film Bruce Almighty, the titular character uses powers endowed by God to manifest Hoffa's body in order to procure a story interesting enough to reclaim his career in the news industry.

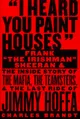

In his book, I Heard You Paint Houses: Frank "The Irishman" Sheeran and the Closing of the Case on Jimmy Hoffa (2004), author Charles Brandt claims that Frank Sheeran, an alleged professional killer for the mob and longtime friend of Hoffa's, confessed to assassinating him.

According to Brandt, O'Brien drove Sheeran, Hoffa, and fellow mobster Sal Briguglio to a house in Detroit.

He claimed that while O'Brien and Briguglio drove off, Sheeran and Hoffa went into the house, where Sheeran claims that he shot Hoffa twice behind the right ear, and that he was told Hoffa was cremated after the murder. Further, Sheeran also admitted later to reporters that he murdered Hoffa, yet, blood stains found in the Detroit house where Sheeran claimed the murder happened were determined not to match Hoffa's DNA.

On June 16, 2006, the Detroit Free Press published in its entirety the so-called "Hoffex Memo", a 56-page report prepared by the FBI for a January 1976 briefing on the case at FBI Headquarters in Washington. Although not claiming conclusively to establish the specifics of his disappearance, the memo records a belief that Hoffa was murdered at the behest of organized crime figures, who regarded his efforts to regain power within the Teamsters as a threat to their control of the union's pension fund.

In Philip Carlo's book The Iceman: Confessions of a Mafia Contract Killer (2006), Richard Kuklinski claimed to know the fate of Hoffa: his body was placed in a 50-gallon drum and set on fire for "a half hour or so", then the drum was welded shut and buried in a junkyard. Later, according to Kuklinski, an accomplice started to talk to federal authorities. Because of fear that he would use the information to try to get out of trouble, the perpetrators had the drum dug up and placed in the trunk of a car, which was then compacted and shipped, along with hundreds of others, to Japan as scrap metal.

Barbara retired as an Associate Circuit Judge in St. Louis County, Missouri, in March 2008.

Barbara agreed to serve under Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster as Chief Counsel of the Division of Civil Disability and Workers Rights.

Hoffa's body was rumored to be buried in Giants Stadium. In an episode of the Discovery Channel show MythBusters, titled "The Hunt for Hoffa", the locations in the stadium where Hoffa was rumored to be buried were scanned with a ground penetrating radar. This was intended to reveal if any disturbances indicated a human body had been buried there. They found no trace of any human remains. In addition, no human remains were found when Giants Stadium was demolished in 2010.

Barbara retired from that post (Chief Counsel of the Division of Civil Disability and Workers Rights) in March 2011.

In 2012, Roseville, Michigan, police took samples from the ground under a suburban Detroit driveway after a person reported having witnessed the burial of a body there around the time of Hoffa's 1975 disappearance. Tests by Michigan State University anthropologists found no evidence of human remains.

In January 2013, reputed gangster Tony Zerilli implied that Hoffa was originally buried in a shallow grave, with the plan to move his remains later to a second location. Zerilli contends that these plans were abandoned. He said Hoffa's remains lay in a field in northern Oakland County, Michigan, not far from the restaurant where he was last seen. Zerilli denied any responsibility for or association with Hoffa's disappearance.

On June 17, 2013, investigation of the Zerilli information led the FBI to a property in Oakland Township in northern Oakland County owned by Detroit mob boss Jack Tocco. After three days, the FBI called off the dig. No human remains were found, and the case remains open.

James Buccellato, a professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Northern Arizona University, suggested in 2017 that Hoffa was likely murdered one mile away from the restaurant at the house of Carlo Licata, the son of mobster Nick Licata. He further suggested that Hoffa's body was taken to a crematorium in Detroit that was owned at the time by the Mafia. He was doubtful the body was transported a long distance, saying "It's just not practical."

In an April 2019 interview with DJ Vlad, former Colombo crime family capo Michael Franzese stated he was aware of the location of Hoffa's body, as well as the shooter. Franzese said Hoffa was definitely killed in a mafia-related hit, and that the order came down from New York. When questioned about the location of Hoffa's body and the shooter, Franzese said, "I can tell you that it's wet, that's for sure," and "Upon good information, again, I think I know who the real shooter was; still alive today, in prison."

In the 2019 Martin Scorsese film The Irishman, which adapts I Heard You Paint Houses, Hoffa is portrayed by Al Pacino.