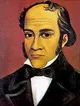

Simón Bolívar was born in a house in Caracas, Captaincy General of Venezuela, on 24 July 1783.

When Bolívar was fourteen, Don Simón Rodríguez was forced to leave the country after being accused of involvement in a conspiracy against the Spanish government in Caracas. Bolívar then entered the military academy of the Milicias de Aragua.

In 1800, he was sent to Spain to follow his military studies in Madrid, where he remained until 1802.

In 1799, following the early deaths of his father Juan Vicente (dead since 1786) and his mother Concepción (who died in 1792), Bolívar traveled to Mexico, France, and Spain, at the age of 16 years, to complete his education. While in Madrid during 1802 and after a two-year courtship, he married María Teresa Rodríguez del Toro y Alaiza, who was to be his only wife. She was related to the aristocratic families of the marquis del Toro of Caracas and the marquis de Inicio of Madrid.

Back in Europe in 1804, Bolívar lived in France and traveled to different countries.

While in Paris, Bolívar witnessed the coronation of Napoleon in Notre Dame, an event that left a profound impression on him. Even if he disagreed with the crowning, he was highly sensitive to the popular veneration inspired by the hero.

Bolívar returned to Venezuela in 1807. After a coup on 19 April 1810, Venezuela achieved de facto independence when the Supreme Junta of Caracas was established and the colonial administrators deposed. The Supreme Junta sent a delegation to Great Britain to get British recognition and aid. This delegation presided by Bolívar also included two future Venezuelan notables Andrés Bello and Luis López Méndez. The trio met with Francisco de Miranda and persuaded him to return to his native land.

In 1811, a delegation from the Supreme Junta, also including Bolívar, and a crowd of commoners enthusiastically received Miranda in La Guaira.

During the insurgence war conducted by Miranda, Bolívar was promoted to colonel and was made commandant of Puerto Cabello the following year, 1812.

As Royalist Frigate Captain Domingo de Monteverde was advancing into republican territory from the west, Bolívar lost control of San Felipe Castle along with its ammunition stores on 30 June 1812. Bolívar then retreated to his estate in San Mateo.

Miranda saw the republican cause as lost and signed a capitulation agreement with Monteverde on 25 July, an action that Bolívar and other revolutionary officers deemed treasonous. In one of Bolívar's most morally dubious acts, he and others arrested Miranda and handed him over to the Spanish Royal Army at the port of La Guaira.

For his apparent services to the Royalist cause, Monteverde granted Bolívar a passport, and Bolívar left for Curaçao on 27 August.

It must be said, though, that Bolívar protested to the Spanish authorities about the reasons why he handled Miranda, insisting that he was not lending a service to the Crown but punishing a defector. In 1813, he was given a military command in Tunja, New Granada (modern-day Colombia), under the direction of the Congress of United Provinces of New Granada, which had formed out of the juntas established in 1810.

This was the beginning of the Admirable Campaign. On 24 May, Bolívar entered Mérida, where he was proclaimed El Libertador ("The Liberator").

This was followed by the occupation of Trujillo on 9 June. Six days later, and as a result of Spanish massacres on independence supporters, Bolívar dictated his famous "Decree of War to the Death", allowing the killing of any Spaniard not actively supporting independence.

Caracas was retaken on 6 August 1813, and Bolívar was ratified as El Libertador, establishing the Second Republic of Venezuela. The following year, because of the rebellion of José Tomás Boves and the fall of the republic, Bolívar returned to New Granada, where he commanded a force for the United Provinces.

Bolívar forces entered Bogotá in 1814 and recaptured the city from the dissenting republican forces of Cundinamarca.

Bolívar intended to march into Cartagena and enlist the aid of local forces in order to capture the Royalist town of Santa Marta.

In 1815, however, after a number of political and military disputes with the government of Cartagena, Bolívar fled to Jamaica, where he was denied support. After an assassination attempt in Jamaica, he fled to Haiti, where he was granted protection. He befriended Alexandre Pétion, the president of the recently independent southern republic (as opposed to the Kingdom of Haiti in the north), and petitioned him for aid.

In 1816, with Haitian soldiers and vital material support, Bolívar landed in Venezuela and fulfilled his promise to Pétion to free Spanish America's slaves on 2 June 1816.

In July 1817, on a second expedition, Bolívar captured Angostura after defeating the counter-attack of Miguel de la Torre. However, Venezuela remained a captaincy of Spain after the victory in 1818 by Pablo Morillo in the Second Battle of La Puerta.

On 15 February 1819, Bolívar was able to open the Venezuelan Second National Congress in Angostura, in which he was elected president and Francisco Antonio Zea was elected vice president. Bolívar then decided that he would first fight for the independence of New Granada, to gain resources of the vice royalty, intending later to consolidate the independence of Venezuela.

The campaign for the independence of New Granada, which included the crossing of the Andes mountain range, one of history's military feats, was consolidated with the victory at the Battle of Boyacá on 7 August 1819.

The Battle of Boyacá (1819), was the decisive battle that ensured the success of Bolívar's campaign to liberate New Granada. The battle of Boyaca is considered the beginning of the independence of the North of South America, and is considered important because it led to the victories of the battle of Carabobo in Venezuela, Pichincha in Ecuador, and Junín and Ayacucho in Peru.

Bolívar returned to Angostura, when congress passed a law forming a greater Republic of Colombia on 17 December, making Bolívar president and Zea vice president, with Francisco de Paula Santander vice president on the New Granada side, and Juan Germán Roscio vice president on the Venezuela side.

Morillo was left in control of Caracas and the coastal highlands.After the restoration of the Cádiz Constitution, Morillo ratified two treaties with Bolívar on 25 November 1820, calling for a six-month armistice and recognizing Bolívar as president of the republic.

Bolívar and Morillo met in San Fernando de Apure on 27 November, after which Morillo left Venezuela for Spain, leaving La Torre in command.

From his newly consolidated base of power, Bolívar launched outright independence campaigns in Venezuela and Ecuador. These campaigns concluded with the victory at the Battle of Carabobo, after which Bolívar triumphantly entered Caracas on 29 June 1821.

On 7 September 1821, Gran Colombia (a state covering much of modern Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela) was created, with Bolívar as president and Santander as vice president.

Bolívar followed with the Battle of Bombona and the Battle of Pichincha, after which he entered Quito on 16 June 1822.

On 26 and 27 July 1822, Bolívar held the Guayaquil Conference with the Argentine General José de San Martín, who had received the title of "Protector of Peruvian Freedom" in August 1821 after partially liberating Peru from the Spanish.

Thereafter, Bolívar took over the task of fully liberating Peru.

The Peruvian congress named him dictator of Peru on 10 February 1824, which allowed Bolívar to reorganize completely the political and military administration. Assisted by Antonio José de Sucre, Bolívar decisively defeated the Spanish cavalry at the Battle of Junín on 6 August 1824. Sucre destroyed the still numerically superior remnants of the Spanish forces at Ayacucho on 9 December 1824.

On 6 August 1825, at the Congress of Upper Peru, the "Republic of Bolivia" was created.

Bolívar is thus one of the few people to have a country named after him. Bolívar returned to Caracas on 12 January 1827, and then back to Bogotá.

Bolívar had great difficulties maintaining control of the vast Gran Colombia. In 1826, internal divisions sparked dissent throughout the nation, and regional uprisings erupted in Venezuela. The new South American union had revealed its fragility and appeared to be on the verge of collapse. To preserve the union, an amnesty was declared and an arrangement was reached with the Venezuelan rebels, but this increased the political dissent in neighboring New Granada. In an attempt to keep the nation together as a single entity, Bolívar called for a constitutional convention at Ocaña in March 1828.

This move was considered controversial in New Granada and was one of the reasons for the deliberations, which met from 9 April to 10 June 1828. The convention almost ended up drafting a document which would have implemented a radically federalist form of government, which would have greatly reduced the powers of a central administration. The federalist faction was able to command a majority for the draft of a new constitution which has definite federal characteristics despite its ostensibly centralist outline. Unhappy with what would be the ensuing result, pro-Bolívar delegates withdrew from the convention, leaving it moribund.

After the facts, Bolivar continued to govern in a rarefied environment, cornered by fractional disputes. Uprisings occurred in New Granada, Venezuela, and Ecuador during the following two years. The separatists accused him of betraying republican principles and of wanting to establish a permanent dictatorship. Gran Colombia declared war against Peru when president General La Mar invaded Guayaquil. He was later defeated by Marshall Antonio José de Sucre in the Battle of the Portete de Tarqui, 27 February 1829. Sucre was killed on 4 June 1830. General Juan José Flores wanted to separate the southern departments (Quito, Guayaquil, and Azuay), known as the District of Ecuador, from Gran Colombia to form an independent country and become its first President. Venezuela was proclaimed independent on 13 January 1830 and José Antonio Páez maintained the presidency of that country, banishing Bolivar.

On 20 January 1830, as his dream fell apart, Bolívar delivered his final address to the nation, announcing that he would be stepping down from the presidency of Gran Colombia. In his speech, a distraught Bolívar urged the people to maintain the union and to be wary of the intentions of those who advocated for separation.

Bolívar finally resigned the presidency on 27 April 1830, intending to leave the country for exile in Europe. He had already sent several crates containing his belongings and writings ahead of him to Europe, but he died before setting sail from Cartagena.

On 17 December 1830, at the age of 47, Simón Bolívar died of tuberculosis in the Quinta de San Pedro Alejandrino in Santa Marta, Gran Colombia (now Colombia).